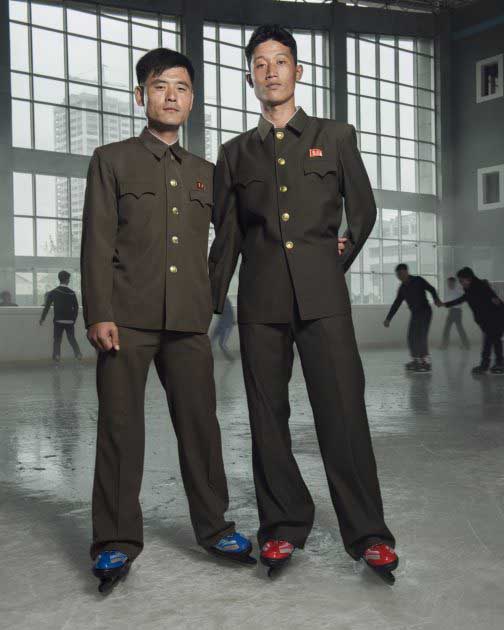

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2018

Kim Yun Gyong, Han Sol Gyong, Kim Won Gyong, Kang Sun Hwa and Kong Su Hyang in the 3D movie theater at SCI Tech Complex.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2018

Kim Yun Gyong, Han Sol Gyong, Kim Won Gyong, Kang Sun Hwa and Kong Su Hyang in the 3D movie theater at SCI Tech Complex.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

Hong Su Jong pose at the Kwangbok, or Liberation, department store in Pyongyang

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

Hong Su Jong pose at the Kwangbok, or Liberation, department store in Pyongyang

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

A family pose behing a painted wall in tribute to the North Korean space programm in front of Munsu water park.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

A family pose behing a painted wall in tribute to the North Korean space programm in front of Munsu water park.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

The doctor Ri Su Rim durinfg a medical examination of Miss Yu Hyang Suk at the Zhenghsu Pyongyang textile factory.

Zhengsu Pyongyang textile factory is North Korea's largest textile factory with 8500 workers which 80% of women

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

The doctor Ri Su Rim durinfg a medical examination of Miss Yu Hyang Suk at the Zhenghsu Pyongyang textile factory.

Zhengsu Pyongyang textile factory is North Korea's largest textile factory with 8500 workers which 80% of women

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2018

Kim Hyang and Kim Ju Hyang pose in the Meari Shooting Range.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2018

Kim Hyang and Kim Ju Hyang pose in the Meari Shooting Range.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

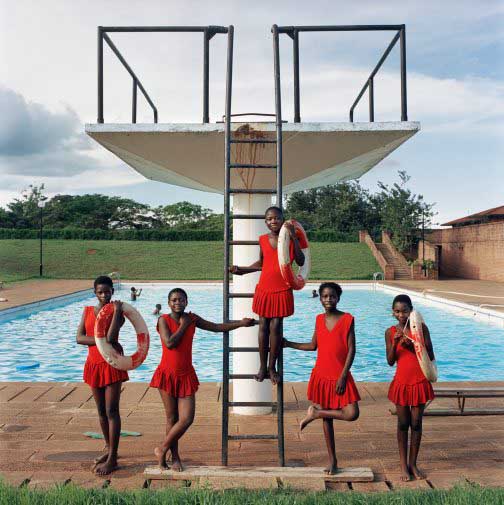

PyongYang October 2017

Kim Gum Sim and Ryu Song Hyang, two workers pose in the swimming pool of the food factory of capital Pyongyang's Mangyongdae district. The fifth floor of a food factory has been turned into a place of fun, the waterpark, complete with pools and basketball hoops, as well as sunloungers, a fish pond, grotto and sauna. On an island in the pool is a huge trophy - an apparent nod to the factory's role making food for the country's athletes. This factory claim to be the coolest workplace worldwide.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

Kim Gum Sim and Ryu Song Hyang, two workers pose in the swimming pool of the food factory of capital Pyongyang's Mangyongdae district. The fifth floor of a food factory has been turned into a place of fun, the waterpark, complete with pools and basketball hoops, as well as sunloungers, a fish pond, grotto and sauna. On an island in the pool is a huge trophy - an apparent nod to the factory's role making food for the country's athletes. This factory claim to be the coolest workplace worldwide.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

During the spring on sunday or during holydays, Pyongyang family like to picnic in Mansudae parc.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

During the spring on sunday or during holydays, Pyongyang family like to picnic in Mansudae parc.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

Bae Yun Gyong, Kim Bok Ryon and Gang Yun Gyong pose behing a plastic wedding buffet in a Pyongyang restaurant

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

Bae Yun Gyong, Kim Bok Ryon and Gang Yun Gyong pose behing a plastic wedding buffet in a Pyongyang restaurant

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2018

Kim Su Ryon in the subway

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2018

Kim Su Ryon in the subway

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

Sariwon October 2017

Farmer's working in Sariwon Coperative farm

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

Sariwon October 2017

Farmer's working in Sariwon Coperative farm

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

Sariwon October 2017

Farmer's working in Sariwon Coperative farm

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

Sariwon October 2017

Farmer's working in Sariwon Coperative farm

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

Yu Gyong Il worker at Pyongyang wire and cable factory

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

Yu Gyong Il worker at Pyongyang wire and cable factory

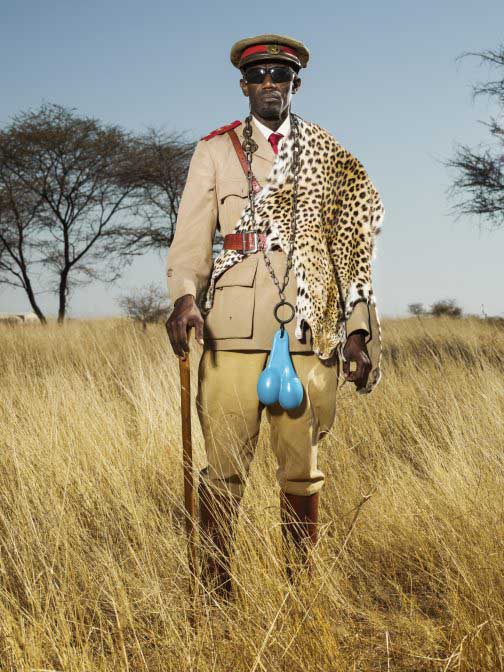

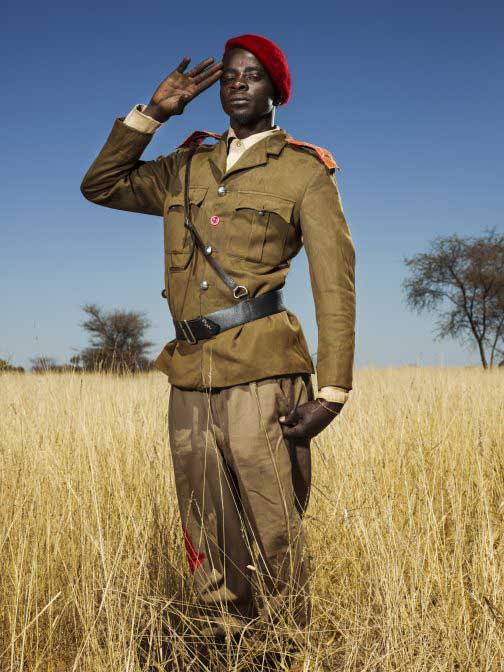

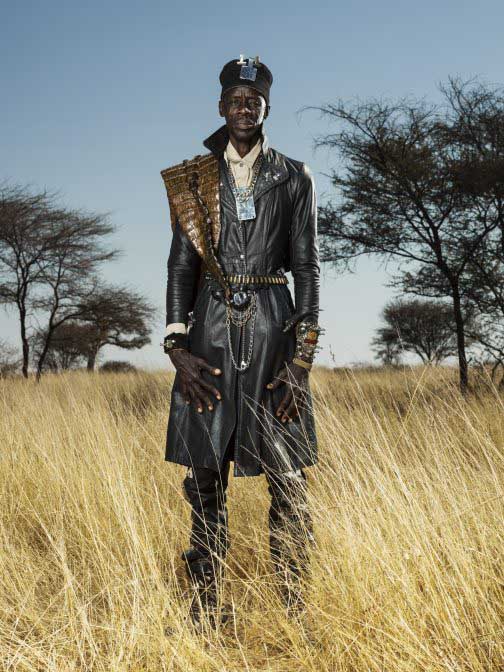

Okahandja,Namibia- (August 2017) :

Dave Veziruapi from Otjonguvi pose in a field.

For the Herero, the ancestor commemoration ceremony are the most commun annual ceremony. The major one take place in Okahandja where most of the famous Herero chief have been buried.

Herero believe in the sacred fire, it's thay to be connected with their ancestor.

For this ceremony everyone get dress with the most amazing uniform, on august 2017 in Okahandja, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Okahandja,Namibia- (August 2017) :

Dave Veziruapi from Otjonguvi pose in a field.

For the Herero, the ancestor commemoration ceremony are the most commun annual ceremony. The major one take place in Okahandja where most of the famous Herero chief have been buried.

Herero believe in the sacred fire, it's thay to be connected with their ancestor.

For this ceremony everyone get dress with the most amazing uniform, on august 2017 in Okahandja, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

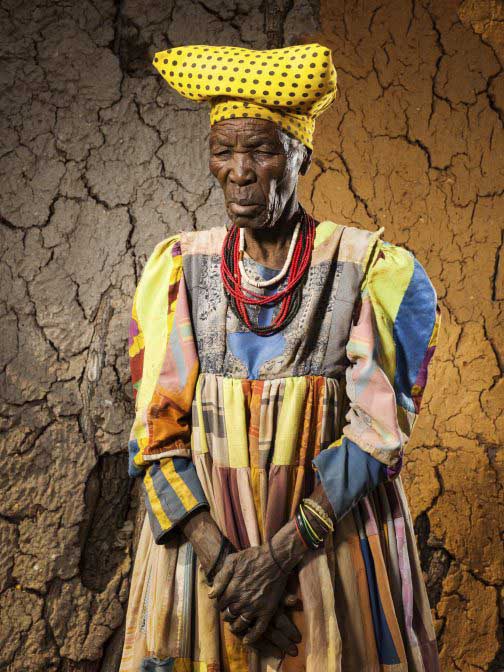

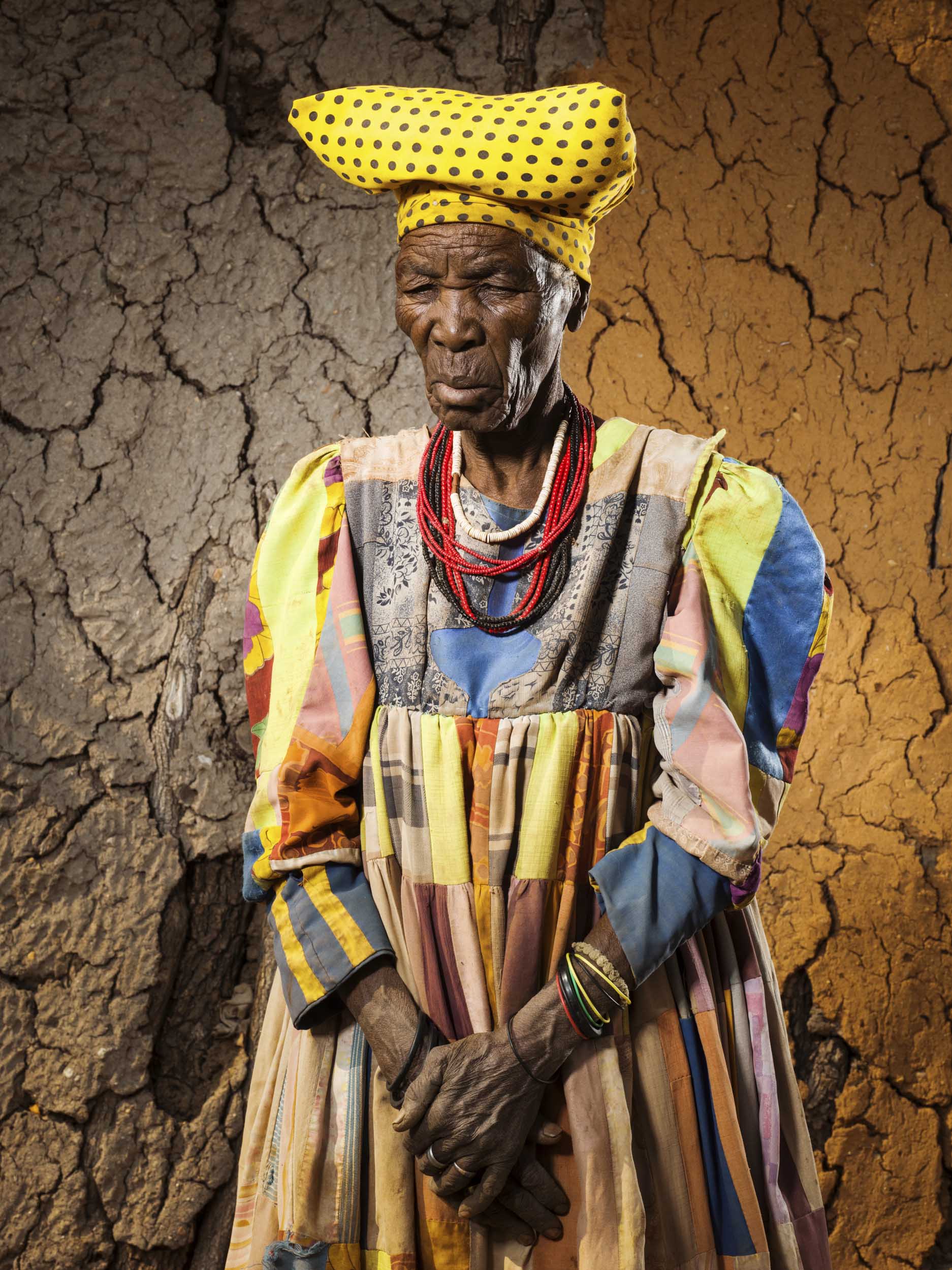

Otavi,Namibia- (August 2017) :

Iseml Mbunguha pose on her daily dress on August 2017 in Otavi, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Otavi,Namibia- (August 2017) :

Iseml Mbunguha pose on her daily dress on August 2017 in Otavi, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

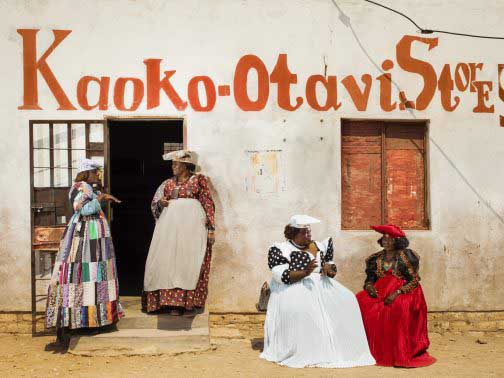

Otjinene,Namibia- (January 2017) : Herero from the local community at the supermarket on january 2017 in Otjinene, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Otjinene,Namibia- (January 2017) : Herero from the local community at the supermarket on january 2017 in Otjinene, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Otjinene,Namibia- (January 2017) : Magdalena Ohomiza et Luder Kanga at Otjinene fuel station on january 2017 in Otjinene, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Otjinene,Namibia- (January 2017) : Magdalena Ohomiza et Luder Kanga at Otjinene fuel station on january 2017 in Otjinene, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Okakarara,Namibia- (January 2017) : Willy (Wilhem) Kaeka, he is wearing a simple costume trouper, on january 2017 in Okakarara, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Okakarara,Namibia- (January 2017) : Willy (Wilhem) Kaeka, he is wearing a simple costume trouper, on january 2017 in Okakarara, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

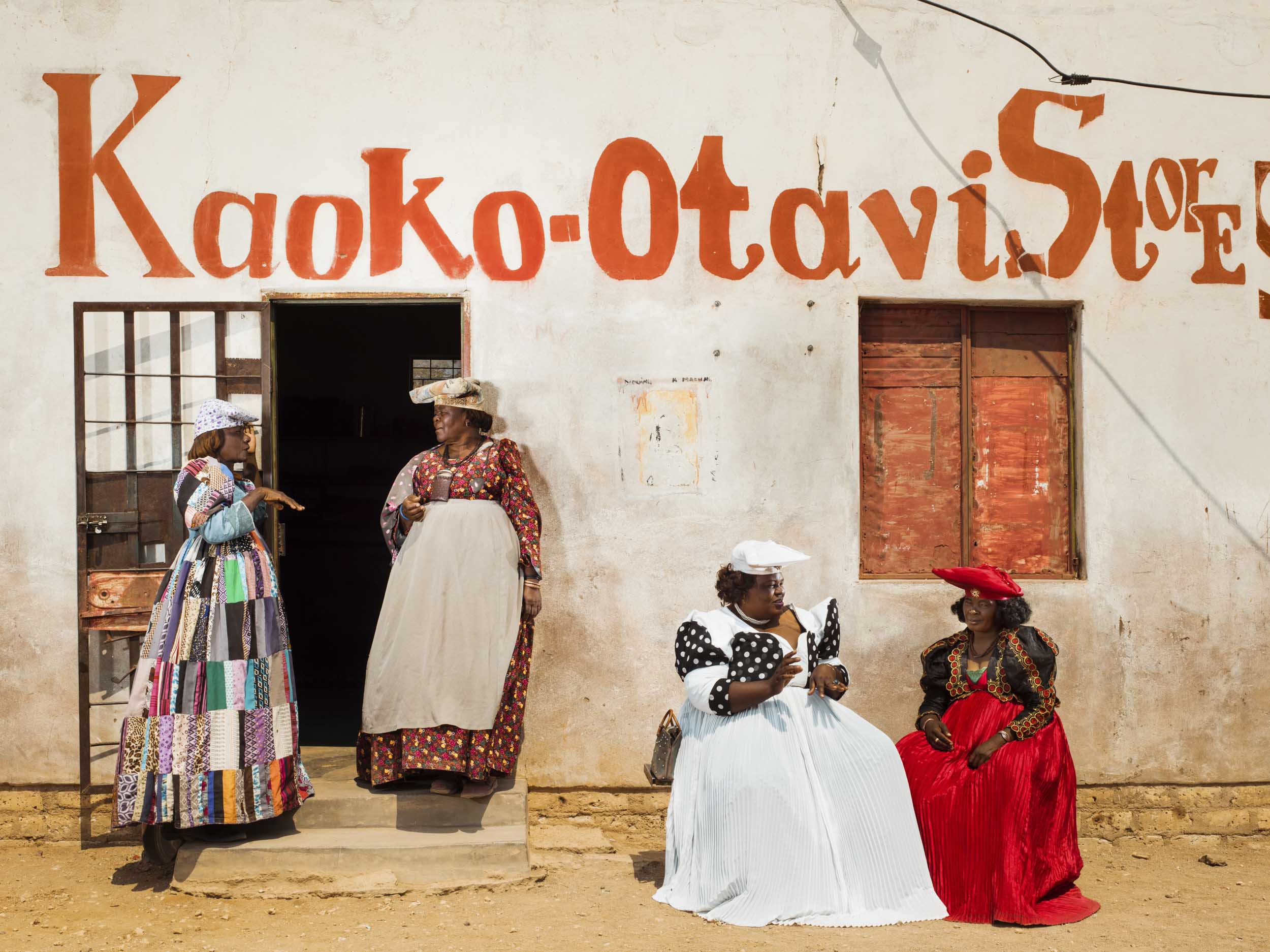

Otavi,Namibia- (August 2017) :

Chat time at the Otavi grocery, on August 2017 in Otavi, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Otavi,Namibia- (August 2017) :

Chat time at the Otavi grocery, on August 2017 in Otavi, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Ondjete,Namibia- (August 2017) :

Tjetuu Mbinge (left) and Verivetiza Mbahuu in their village and family compound on August 2017 in Ondjete, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Ondjete,Namibia- (August 2017) :

Tjetuu Mbinge (left) and Verivetiza Mbahuu in their village and family compound on August 2017 in Ondjete, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

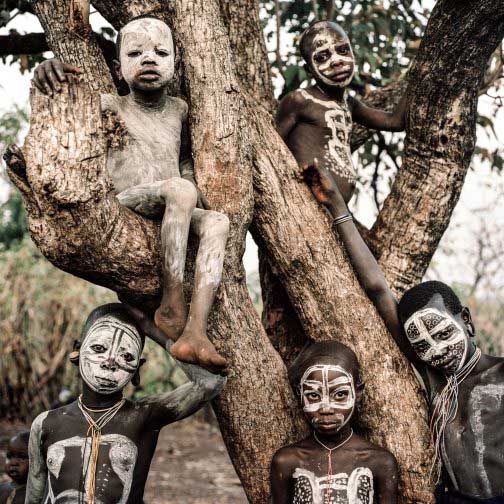

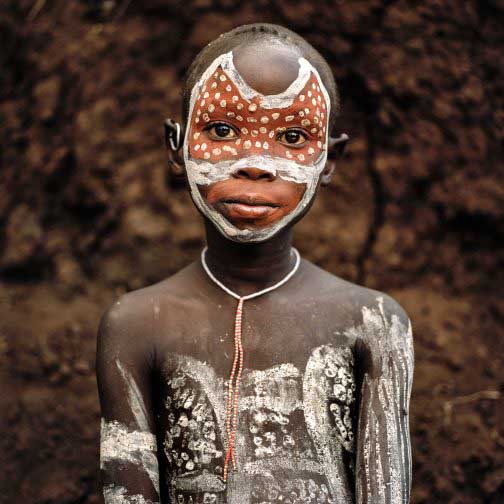

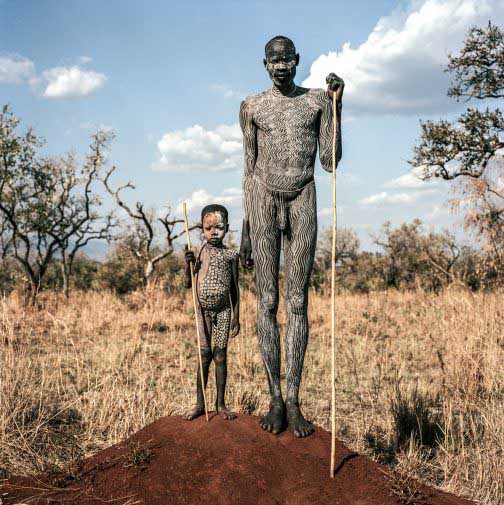

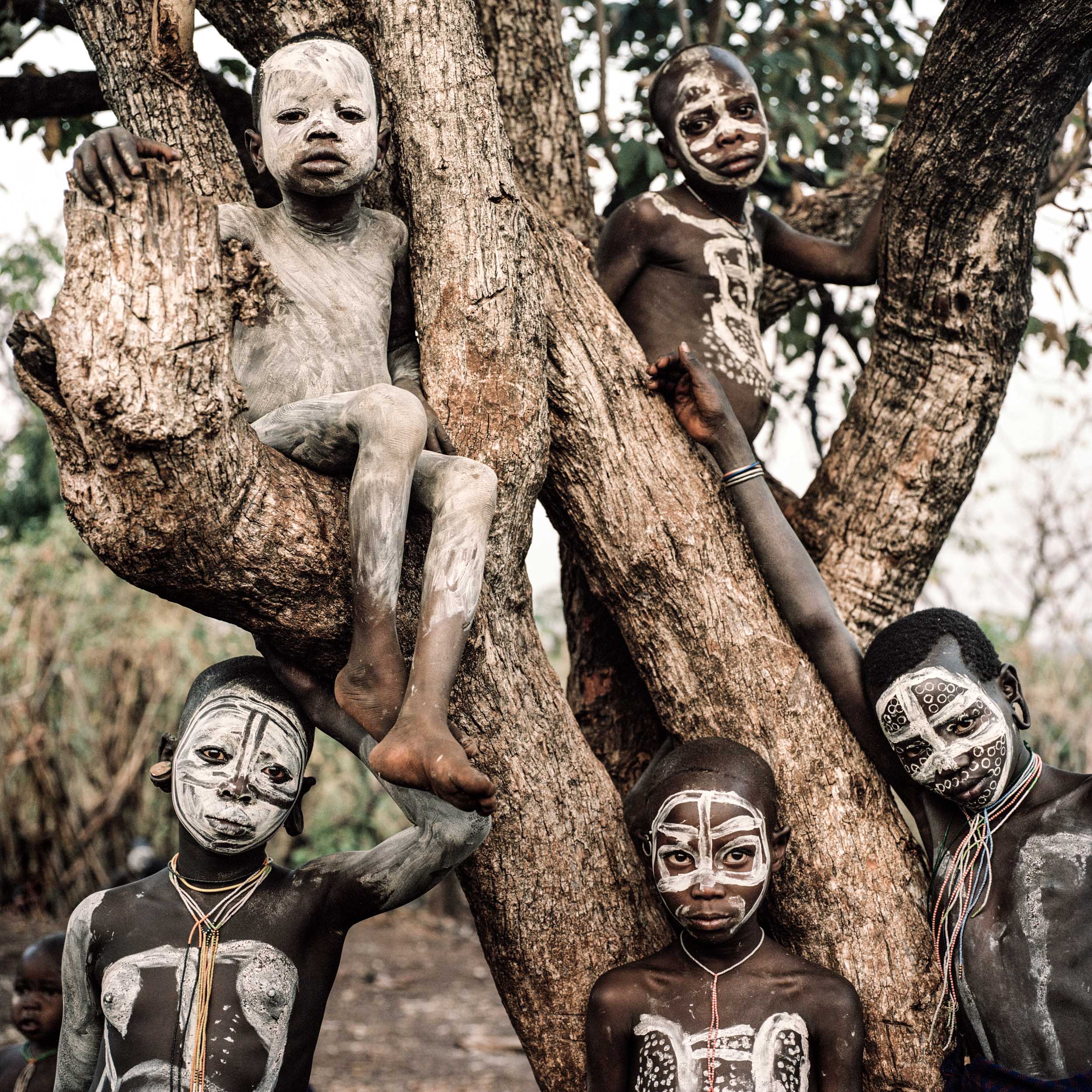

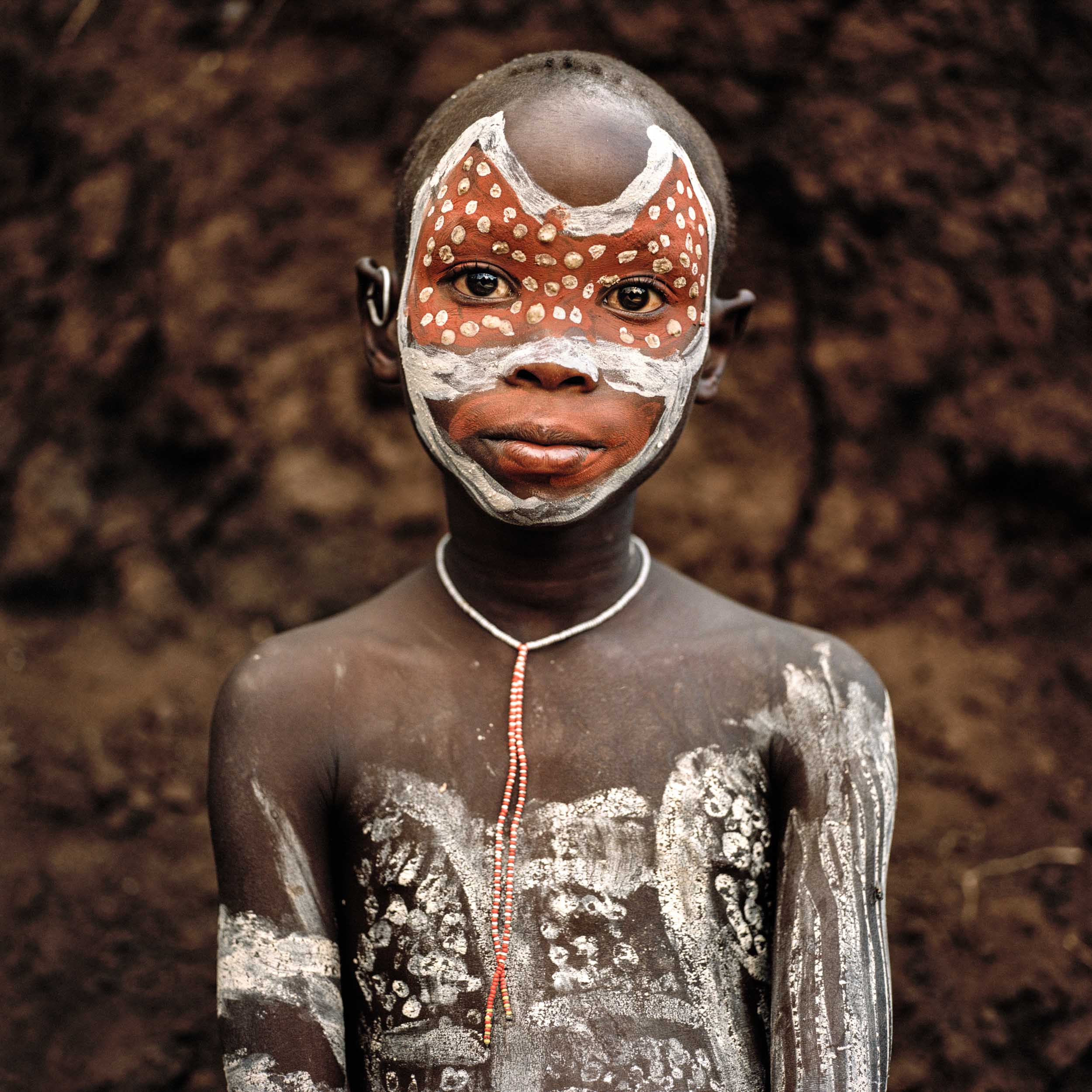

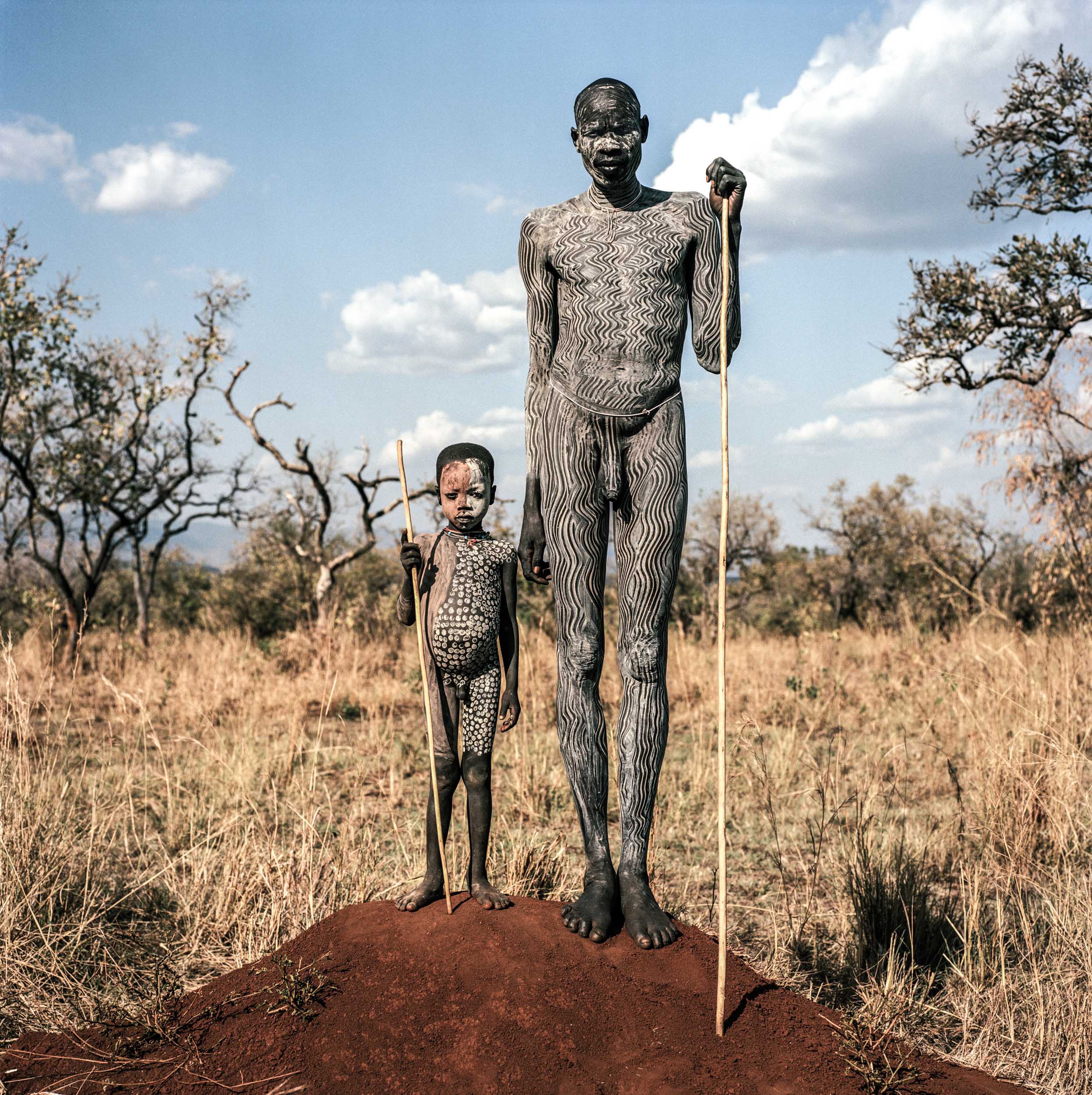

Les Surmas appelé aussi Suri sont des habitants du sud de l'Éthiopie vivant dans la vallée de l'Omo. Les Suris pratiquent des modifications corporelles, telles que les peintures rituelles et le port de labrets chez les femmes. Encouragés dès leur plus jeune âge à imiter les adultes, les enfants Surma s’enduisent le corps et le visage de pâtes calcaires diversement pigmentées suivant la roche utilisée, selon des contours d’une extrême fantaisie. Certains motifs font allusion à la nature ou aux animaux : robes des vaches, faciès des singes colobes, pelage des prédateurs… Lorsque plusieurs personnes se peignent de façon identique, cela signifie qu’ils sont liés familialement ou d’amitié. Ces décorations répondent à un code social bien établi, et il existe diverses façons de se peindre selon le but recherché : séduction ou peintures de guerre devant effrayer l’ennemi. La coiffure est un autre élément prépondérant dans la fierté des guerriers Surma. Ils se rasent le crâne avec des lames de rasoir en laissant quelques lignes décoratives.

La largeur du labret donne une estimation de la dot dont aura à s’acquitter tout prétendant. La dot peut représenter jusqu’à une soixantaine de bêtes. Les labrets en bois peuvent être de forme trapézoïdale ou demi sphérique, tandis que ceux en argile seront généralement ronds. En âge de se marier, la jeune fille Surma, après s’être fait percer sa lèvre et extraire des dents de la mâchoire inférieure, mettra tout en œuvre pour distendre cet orifice en y insérant des labrets successifs, de taille toujours croissante. En général, toutes les filles d’une classe d’âge se font inciser en même temps, et lorsque la coupure pratiquée a cicatrisée, le village célèbre cet événement par une fête nommée Zigroo. On y boit le bordray, sorte de boisson fermentée à base de farines de sorgho et de maïs blanc.

Pour les hommes, il est d’usage de procéder à des scarific

Les Surmas appelé aussi Suri sont des habitants du sud de l'Éthiopie vivant dans la vallée de l'Omo. Les Suris pratiquent des modifications corporelles, telles que les peintures rituelles et le port de labrets chez les femmes. Encouragés dès leur plus jeune âge à imiter les adultes, les enfants Surma s’enduisent le corps et le visage de pâtes calcaires diversement pigmentées suivant la roche utilisée, selon des contours d’une extrême fantaisie. Certains motifs font allusion à la nature ou aux animaux : robes des vaches, faciès des singes colobes, pelage des prédateurs… Lorsque plusieurs personnes se peignent de façon identique, cela signifie qu’ils sont liés familialement ou d’amitié. Ces décorations répondent à un code social bien établi, et il existe diverses façons de se peindre selon le but recherché : séduction ou peintures de guerre devant effrayer l’ennemi. La coiffure est un autre élément prépondérant dans la fierté des guerriers Surma. Ils se rasent le crâne avec des lames de rasoir en laissant quelques lignes décoratives.

La largeur du labret donne une estimation de la dot dont aura à s’acquitter tout prétendant. La dot peut représenter jusqu’à une soixantaine de bêtes. Les labrets en bois peuvent être de forme trapézoïdale ou demi sphérique, tandis que ceux en argile seront généralement ronds. En âge de se marier, la jeune fille Surma, après s’être fait percer sa lèvre et extraire des dents de la mâchoire inférieure, mettra tout en œuvre pour distendre cet orifice en y insérant des labrets successifs, de taille toujours croissante. En général, toutes les filles d’une classe d’âge se font inciser en même temps, et lorsque la coupure pratiquée a cicatrisée, le village célèbre cet événement par une fête nommée Zigroo. On y boit le bordray, sorte de boisson fermentée à base de farines de sorgho et de maïs blanc.

Pour les hommes, il est d’usage de procéder à des scarific

Les Surmas appelé aussi Suri sont des habitants du sud de l'Éthiopie vivant dans la vallée de l'Omo. Les Suris pratiquent des modifications corporelles, telles que les peintures rituelles et le port de labrets chez les femmes. Encouragés dès leur plus jeune âge à imiter les adultes, les enfants Surma s’enduisent le corps et le visage de pâtes calcaires diversement pigmentées suivant la roche utilisée, selon des contours d’une extrême fantaisie. Certains motifs font allusion à la nature ou aux animaux : robes des vaches, faciès des singes colobes, pelage des prédateurs… Lorsque plusieurs personnes se peignent de façon identique, cela signifie qu’ils sont liés familialement ou d’amitié. Ces décorations répondent à un code social bien établi, et il existe diverses façons de se peindre selon le but recherché : séduction ou peintures de guerre devant effrayer l’ennemi. La coiffure est un autre élément prépondérant dans la fierté des guerriers Surma. Ils se rasent le crâne avec des lames de rasoir en laissant quelques lignes décoratives.

La largeur du labret donne une estimation de la dot dont aura à s’acquitter tout prétendant. La dot peut représenter jusqu’à une soixantaine de bêtes. Les labrets en bois peuvent être de forme trapézoïdale ou demi sphérique, tandis que ceux en argile seront généralement ronds. En âge de se marier, la jeune fille Surma, après s’être fait percer sa lèvre et extraire des dents de la mâchoire inférieure, mettra tout en œuvre pour distendre cet orifice en y insérant des labrets successifs, de taille toujours croissante. En général, toutes les filles d’une classe d’âge se font inciser en même temps, et lorsque la coupure pratiquée a cicatrisée, le village célèbre cet événement par une fête nommée Zigroo. On y boit le bordray, sorte de boisson fermentée à base de farines de sorgho et de maïs blanc.

Pour les hommes, il est d’usage de procéder à des scarific

Les Surmas appelé aussi Suri sont des habitants du sud de l'Éthiopie vivant dans la vallée de l'Omo. Les Suris pratiquent des modifications corporelles, telles que les peintures rituelles et le port de labrets chez les femmes. Encouragés dès leur plus jeune âge à imiter les adultes, les enfants Surma s’enduisent le corps et le visage de pâtes calcaires diversement pigmentées suivant la roche utilisée, selon des contours d’une extrême fantaisie. Certains motifs font allusion à la nature ou aux animaux : robes des vaches, faciès des singes colobes, pelage des prédateurs… Lorsque plusieurs personnes se peignent de façon identique, cela signifie qu’ils sont liés familialement ou d’amitié. Ces décorations répondent à un code social bien établi, et il existe diverses façons de se peindre selon le but recherché : séduction ou peintures de guerre devant effrayer l’ennemi. La coiffure est un autre élément prépondérant dans la fierté des guerriers Surma. Ils se rasent le crâne avec des lames de rasoir en laissant quelques lignes décoratives.

La largeur du labret donne une estimation de la dot dont aura à s’acquitter tout prétendant. La dot peut représenter jusqu’à une soixantaine de bêtes. Les labrets en bois peuvent être de forme trapézoïdale ou demi sphérique, tandis que ceux en argile seront généralement ronds. En âge de se marier, la jeune fille Surma, après s’être fait percer sa lèvre et extraire des dents de la mâchoire inférieure, mettra tout en œuvre pour distendre cet orifice en y insérant des labrets successifs, de taille toujours croissante. En général, toutes les filles d’une classe d’âge se font inciser en même temps, et lorsque la coupure pratiquée a cicatrisée, le village célèbre cet événement par une fête nommée Zigroo. On y boit le bordray, sorte de boisson fermentée à base de farines de sorgho et de maïs blanc.

Pour les hommes, il est d’usage de procéder à des scarific

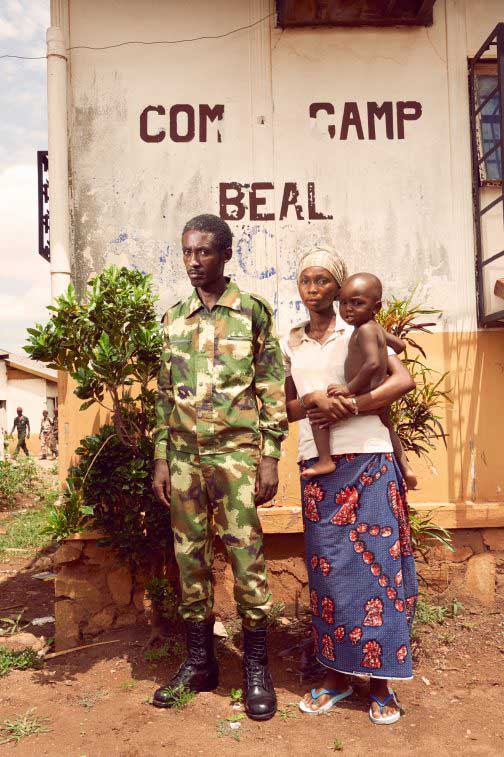

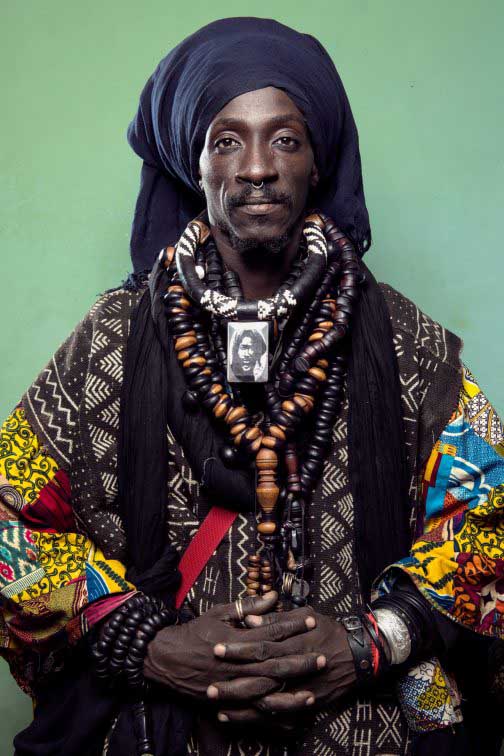

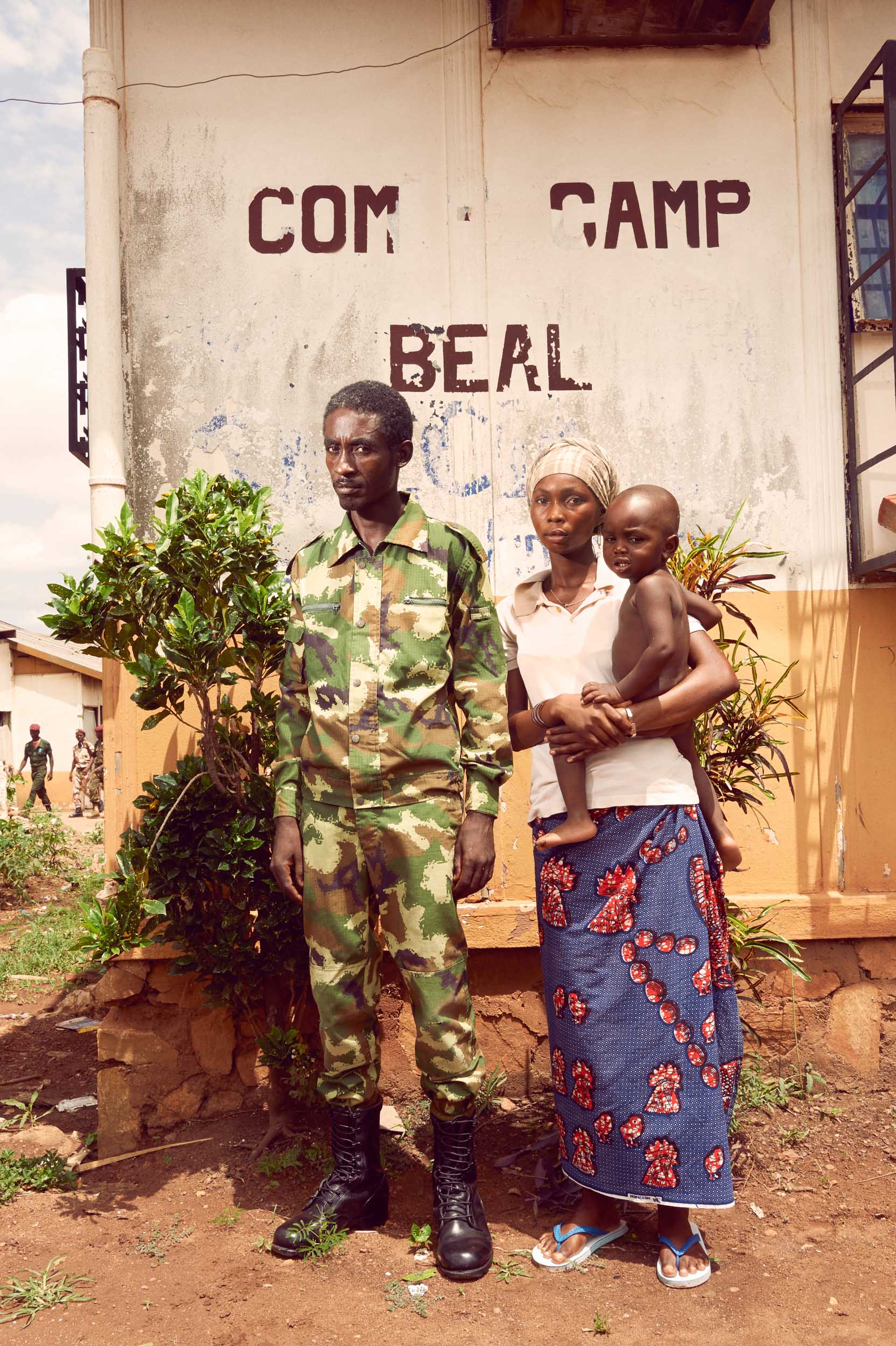

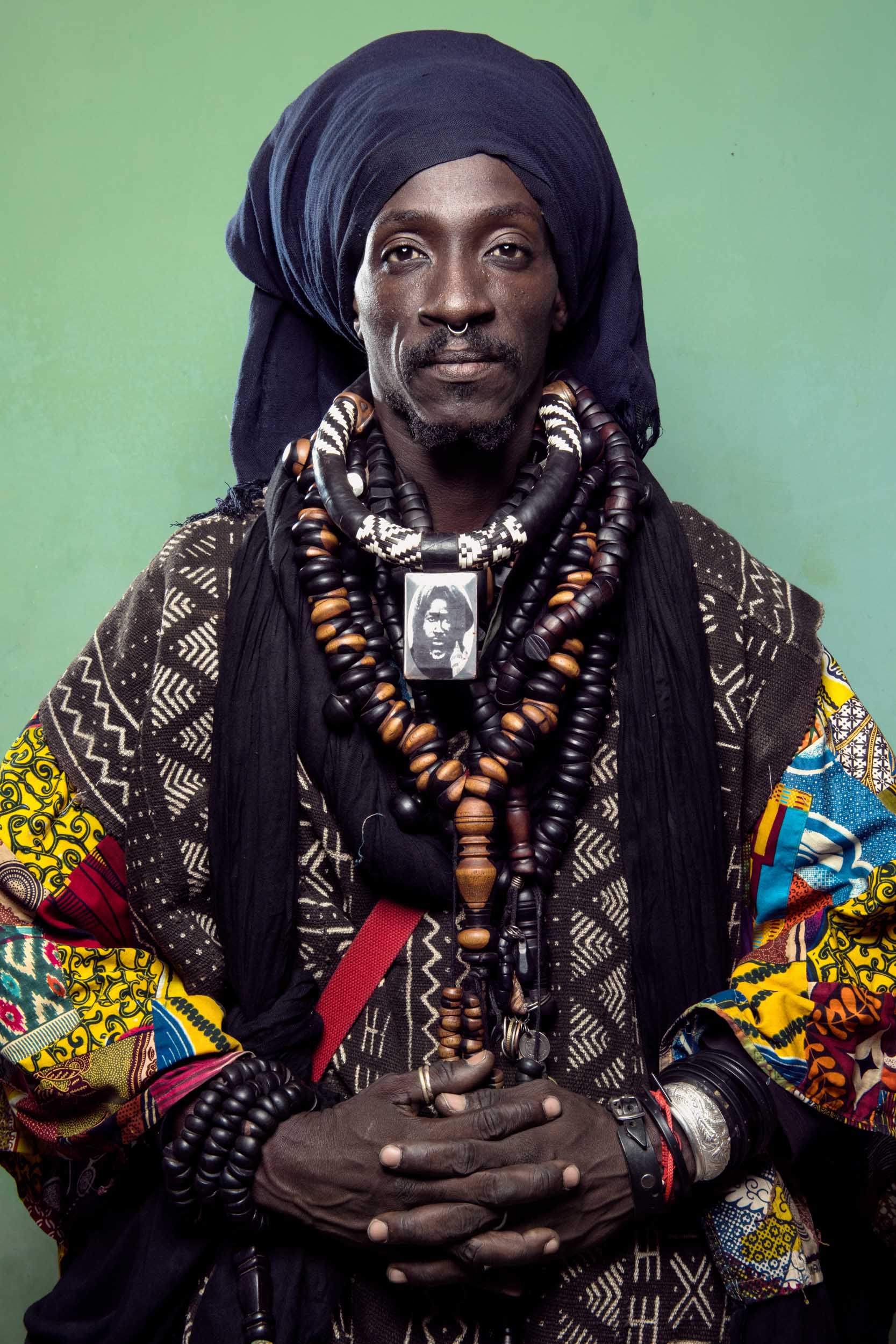

Les Maï-Maï, ou parfois Mayi-Mayi, est un terme général décrivant des groupes armés actifs au cours de la Deuxième guerre du Congo en République démocratique du Congo (RDC).

Le terme Maï-Maï provient de Maï ou Maji, eau dans les langues bantoues de la région. Il fait référence à la révolte Maji Maji intervenue en 1905-1907 au Tanganyika, lors du mouvement populaire de rébellion contre l'occupant allemand dont les combattants étaient protégés par les propriétés magiques de l'eau.

Les guerriers Maï-Maï se croient invulnérables aux armes à feu. Ils s'aspergent d'une potion magique censée faire couler les balles sur leur corps comme de l'eau (maï en swahili).

La plupart se constituèrent pour résister à l'invasion des forces armées du Rwanda. Ils ont été actifs dans les provinces du Nord-Kivu et du Sud-Kivu.

Bien que les Kivus aient été militarisés de longue date, en particulier parmi les minorités Batembo et Bembes, l'instabilité dans la région amena les habitants à constituer les milices Maï-Maï. Que ce soit en tant que groupe unis ou en tant que groupes individuels.

Les groupes repris sous l'appellation « Maï-Maï » incluent des forces armées dirigées par des seigneurs de guerre, des chefs tribaux traditionnels, des chefs de village, et des dirigeants politiques locaux.

Les Maï-Maï, ou parfois Mayi-Mayi, est un terme général décrivant des groupes armés actifs au cours de la Deuxième guerre du Congo en République démocratique du Congo (RDC).

Le terme Maï-Maï provient de Maï ou Maji, eau dans les langues bantoues de la région. Il fait référence à la révolte Maji Maji intervenue en 1905-1907 au Tanganyika, lors du mouvement populaire de rébellion contre l'occupant allemand dont les combattants étaient protégés par les propriétés magiques de l'eau.

Les guerriers Maï-Maï se croient invulnérables aux armes à feu. Ils s'aspergent d'une potion magique censée faire couler les balles sur leur corps comme de l'eau (maï en swahili).

La plupart se constituèrent pour résister à l'invasion des forces armées du Rwanda. Ils ont été actifs dans les provinces du Nord-Kivu et du Sud-Kivu.

Bien que les Kivus aient été militarisés de longue date, en particulier parmi les minorités Batembo et Bembes, l'instabilité dans la région amena les habitants à constituer les milices Maï-Maï. Que ce soit en tant que groupe unis ou en tant que groupes individuels.

Les groupes repris sous l'appellation « Maï-Maï » incluent des forces armées dirigées par des seigneurs de guerre, des chefs tribaux traditionnels, des chefs de village, et des dirigeants politiques locaux.

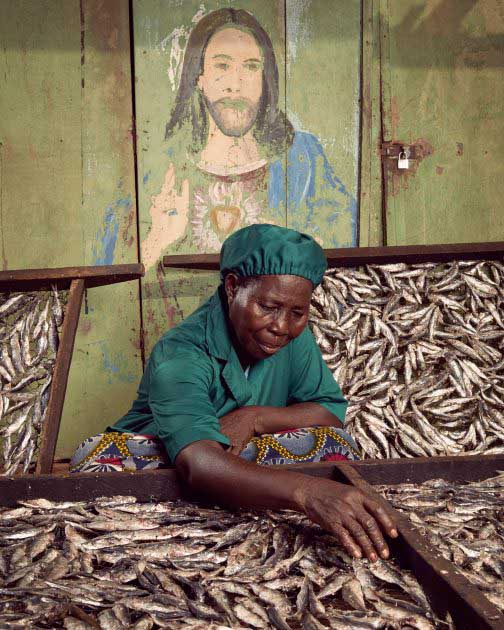

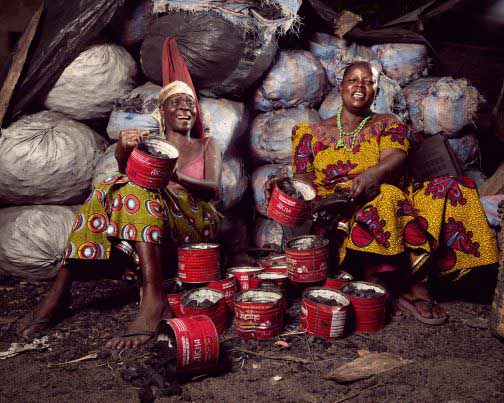

In Togo, 80 percent of the fish that is eaten is smoked over charcoal, a procedure extremely harmful to health. Thanks to support from the World Bank, the women who smoke fish in Katanga, a fishing village near the port of Lomé, Togo capital, now have a modern processing device that allows them to cure the fish without damaging their health. The new method filters out the smoke and produces better-quality fish. Traditional curing generated large amounts of smoke and led to eye and lung diseases in many of the processors (largely women). The traditional smoking technique also posed a danger to the consumer from the harmful particles deposited on the fish. It remains to be seen whether the Togolese, who love smoked fish but are used to the dark color imbued by the customary smoking method, will go for the healthier option.

In Togo, 80 percent of the fish that is eaten is smoked over charcoal, a procedure extremely harmful to health. Thanks to support from the World Bank, the women who smoke fish in Katanga, a fishing village near the port of Lomé, Togo capital, now have a modern processing device that allows them to cure the fish without damaging their health. The new method filters out the smoke and produces better-quality fish. Traditional curing generated large amounts of smoke and led to eye and lung diseases in many of the processors (largely women). The traditional smoking technique also posed a danger to the consumer from the harmful particles deposited on the fish. It remains to be seen whether the Togolese, who love smoked fish but are used to the dark color imbued by the customary smoking method, will go for the healthier option.

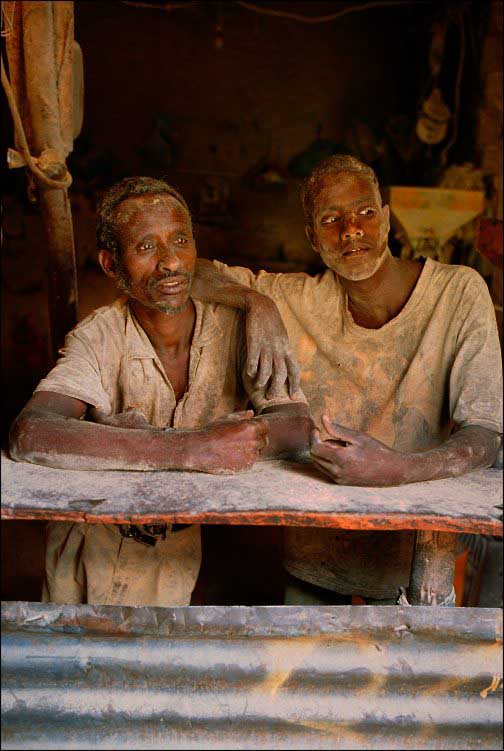

Afrique du Sud

R�gion du Drakensberg

Janvier 2017

Vendeur et vendeuse sur le march� de Emmaus

Afrique du Sud

R�gion du Drakensberg

Janvier 2017

Vendeur et vendeuse sur le march� de Emmaus

Brésil

Rio de Janeiro

Septembre 2015

Brésil

Rio de Janeiro

Septembre 2015

La famille Aquelbec

Aquelbek et Narguiza

Situé à 3000 mètres d'altitude, le lac Song-Kul acceuille les nomades de mai à septembre. Il y laisse paître les troupeaux de vaches, moutons et chevaux, leur principale richesse et la principale source de leur alimentation

La famille Aquelbec

Aquelbek et Narguiza

Situé à 3000 mètres d'altitude, le lac Song-Kul acceuille les nomades de mai à septembre. Il y laisse paître les troupeaux de vaches, moutons et chevaux, leur principale richesse et la principale source de leur alimentation

Les femmes ont parfois seules, les maris sont restés à la ville et elle s'occupe du troupeau dans les hauts alpages

Situé à 3000 mètres d'altitude, le lac Song-Kul acceuille les nomades de mai à septembre. Il y laisse paître les troupeaux de vaches, moutons et chevaux, leur principale richesse et la principale source de leur alimentation.

Les femmes ont parfois seules, les maris sont restés à la ville et elle s'occupe du troupeau dans les hauts alpages

Situé à 3000 mètres d'altitude, le lac Song-Kul acceuille les nomades de mai à septembre. Il y laisse paître les troupeaux de vaches, moutons et chevaux, leur principale richesse et la principale source de leur alimentation.

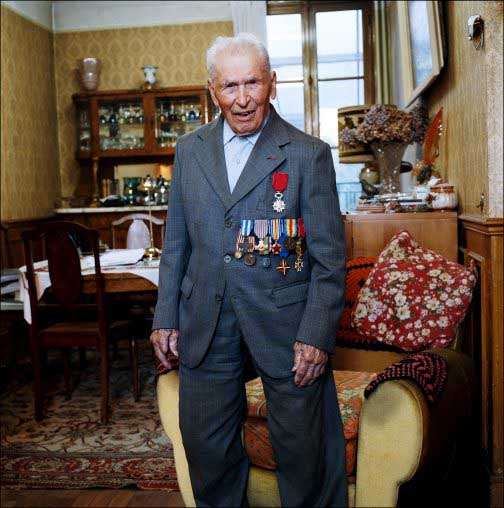

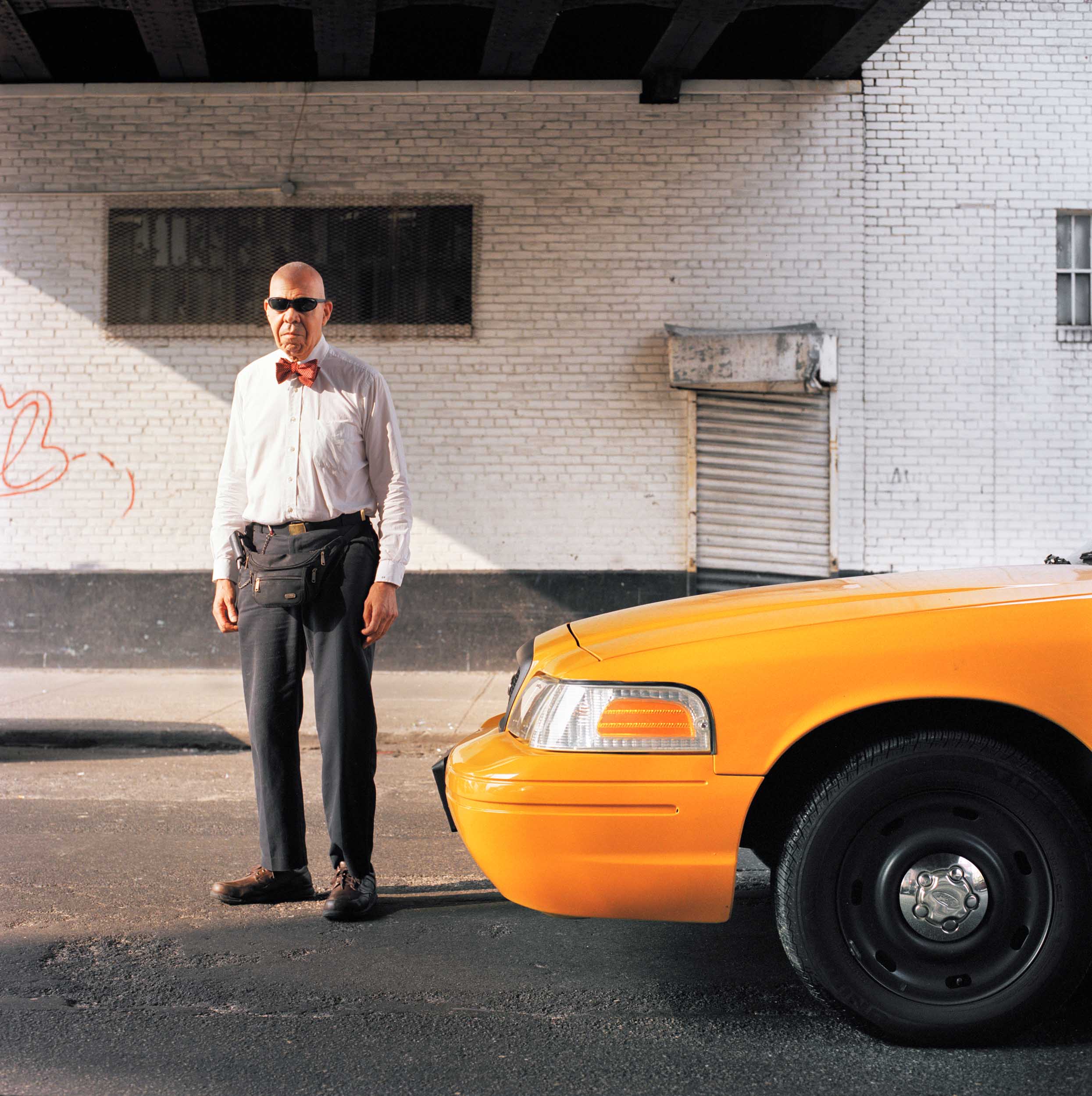

WORLD WAR II VETERAN

USA/OHIO/APRIL 2014

MARION GRAY,SEATTED IN FRONT OF ONE OF THE LAST LANDING CRAFT FROM THE 6 JUNE 1944. MARION WAS MEDIC WITH THE 29TH INFANTRY DIVISION, SGT. GRAY WAS THE FIRST FRANKLIN COUNTY MAN TO BE WOUNDED IN BATTLE AT OMAHA BEACH IN NORMANDY ON D-DAY, JUNE 6, 1944, WHERE HE TOOK SHRAPNEL IN BOTH AN ARM AND A LEG.

WORLD WAR II VETERAN

USA/OHIO/APRIL 2014

MARION GRAY,SEATTED IN FRONT OF ONE OF THE LAST LANDING CRAFT FROM THE 6 JUNE 1944. MARION WAS MEDIC WITH THE 29TH INFANTRY DIVISION, SGT. GRAY WAS THE FIRST FRANKLIN COUNTY MAN TO BE WOUNDED IN BATTLE AT OMAHA BEACH IN NORMANDY ON D-DAY, JUNE 6, 1944, WHERE HE TOOK SHRAPNEL IN BOTH AN ARM AND A LEG.

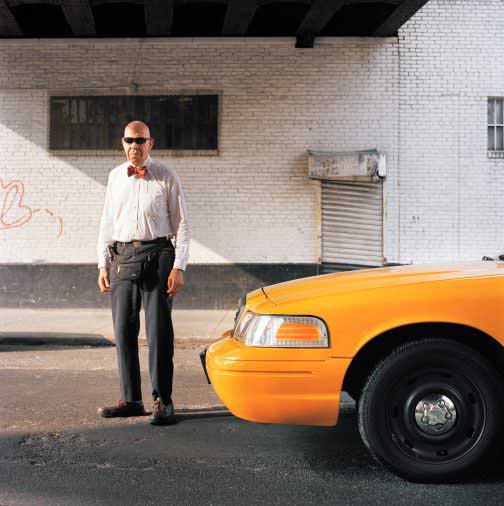

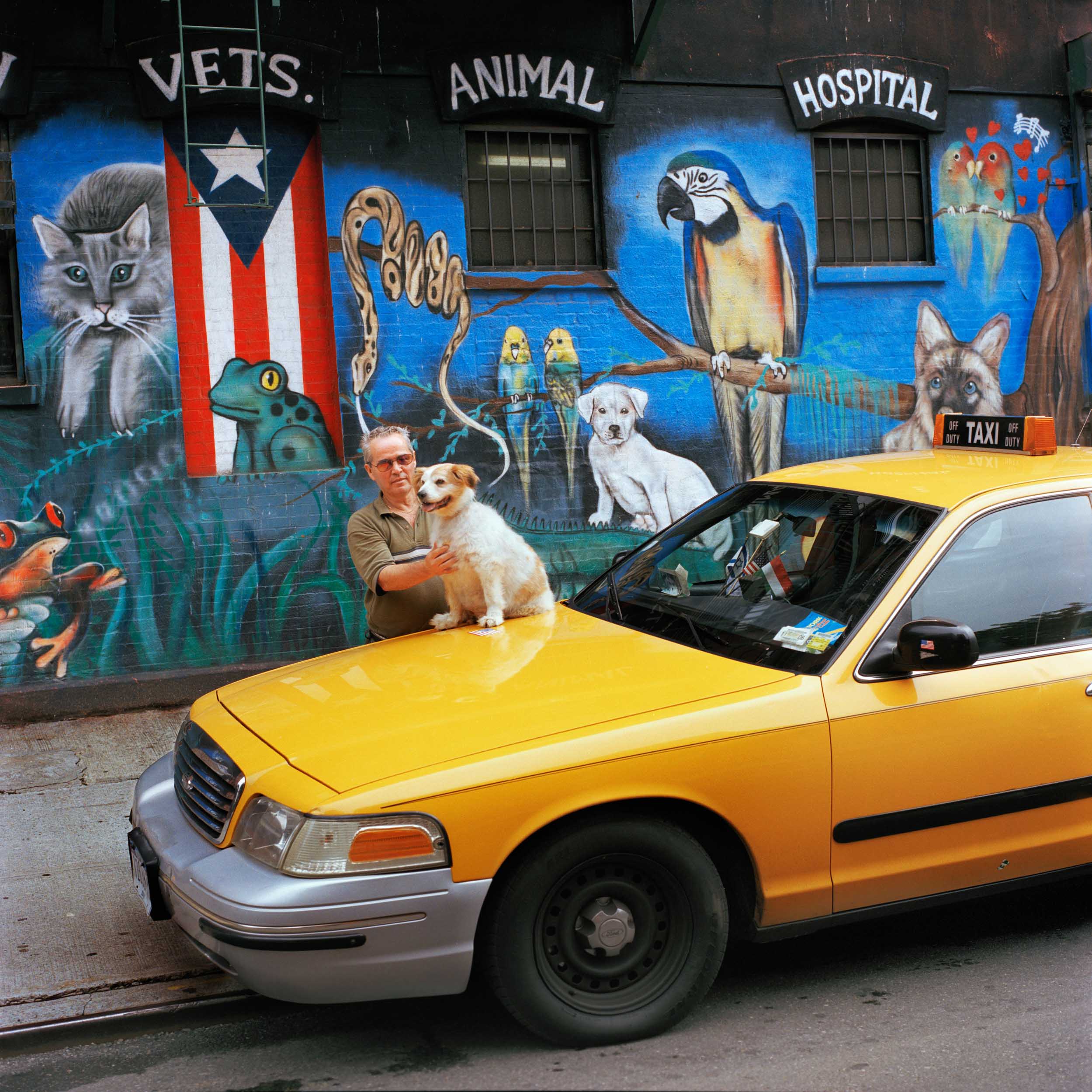

WORLD WAR II VETERAN

FRANCE/ARROMANCHES/MAY 2014

DAVID MYLCHREEST, BRITISH OFFICER FROM THE 43rd INFANTRY DIVISION WESSEX IN FRONT OF A WILLIS JEEP ON ARROMANCHES BEACH WHERE HE LANDED THE 12 JUNE 1944. HE WAS VOLUNTEER FOR THE D-DAY.

WORLD WAR II VETERAN

FRANCE/ARROMANCHES/MAY 2014

DAVID MYLCHREEST, BRITISH OFFICER FROM THE 43rd INFANTRY DIVISION WESSEX IN FRONT OF A WILLIS JEEP ON ARROMANCHES BEACH WHERE HE LANDED THE 12 JUNE 1944. HE WAS VOLUNTEER FOR THE D-DAY.

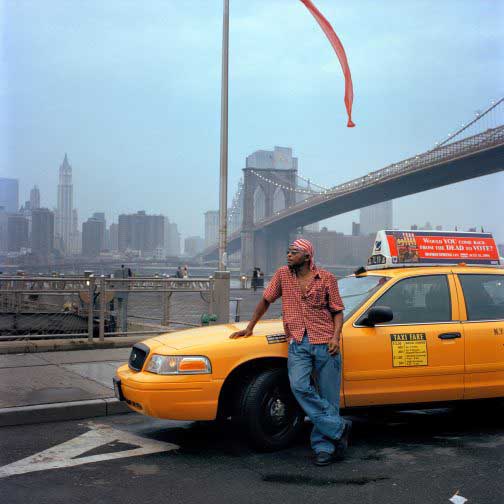

WORLD WAR II VETERAN

USA/MICHIGAN/APRIL 2014

DONALD BURGETT FROM THE 506TH PARACHUTE REGIMENT 101ST AIRBORNE READY TO JUMP AT THE DOOR OF A STILL FLYING C-47 IN AN US ARMY BASE IN MICHIGAN.

WORLD WAR II VETERAN

USA/MICHIGAN/APRIL 2014

DONALD BURGETT FROM THE 506TH PARACHUTE REGIMENT 101ST AIRBORNE READY TO JUMP AT THE DOOR OF A STILL FLYING C-47 IN AN US ARMY BASE IN MICHIGAN.

World War II Veteran

USA/OHIO/APRIl 1944

DONALD JAKEWAY, FROM THE 508 PARACHUTE REGIMENT, 82ND AIRBORNE.

Jakeway landed in a tree near a church building, he said, about 15 miles from Utah Beach. It took 10 days to find anyone else from the 82nd Airborne Division,

World War II Veteran

USA/OHIO/APRIl 1944

DONALD JAKEWAY, FROM THE 508 PARACHUTE REGIMENT, 82ND AIRBORNE.

Jakeway landed in a tree near a church building, he said, about 15 miles from Utah Beach. It took 10 days to find anyone else from the 82nd Airborne Division,

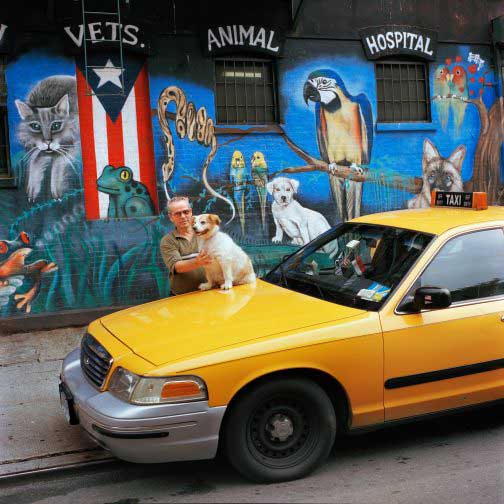

WORLD WAR II VETERANS

FRANCE/OUISTREHAM/APRIL 2014

LEON GAUTHIER, FRENCH COMMANDO N�4 IN HIS BATTLE DRESS SEATTED EXACTLY WHERE HE LANDED 70 YEARS AGO, THE 6 TH JUNE 1944 ON THE BEACH OF COLLEVILLE.

LEON GAUTHIER MEMBRE DES COMMANDOS N�4 EN TENUE COMBAT DE COMMANDO SUR LA PLAGE DE COLLEVILLE A OUISTREHAM A L'ENDROIT OU IL A DEBARQUE IL Y A 70 ANS, LE 6 JUIN 1944

WORLD WAR II VETERANS

FRANCE/OUISTREHAM/APRIL 2014

LEON GAUTHIER, FRENCH COMMANDO N�4 IN HIS BATTLE DRESS SEATTED EXACTLY WHERE HE LANDED 70 YEARS AGO, THE 6 TH JUNE 1944 ON THE BEACH OF COLLEVILLE.

LEON GAUTHIER MEMBRE DES COMMANDOS N�4 EN TENUE COMBAT DE COMMANDO SUR LA PLAGE DE COLLEVILLE A OUISTREHAM A L'ENDROIT OU IL A DEBARQUE IL Y A 70 ANS, LE 6 JUIN 1944

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

A group of woman during a mass dance rehearsal in front of the monument to the Party foudation.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

A group of woman during a mass dance rehearsal in front of the monument to the Party foudation.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2018

Jo Hyang Mi, Jang Yun Hui, Ri Un Bok, Kim Bok Sin, choe Hyong Ju pose in the ship restaurant uniform in front of the tower of the juche idea

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2018

Jo Hyang Mi, Jang Yun Hui, Ri Un Bok, Kim Bok Sin, choe Hyong Ju pose in the ship restaurant uniform in front of the tower of the juche idea

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

A young couple standing on Kim Il Sung Square.

PyongYang central square is famous for the North Korean massif military parades. The square is ringed by austere-loocking buildings.

The most impressive one is the Grand People Study House, the country largest library and national centre of Juche

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

A young couple standing on Kim Il Sung Square.

PyongYang central square is famous for the North Korean massif military parades. The square is ringed by austere-loocking buildings.

The most impressive one is the Grand People Study House, the country largest library and national centre of Juche

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

A group of workers pose in the swimming pool of the food factory of capital Pyongyang's Mangyongdae district. The fifth floor of a food factory has been turned into a place of fun, the waterpark, complete with pools and basketball hoops, as well as sunloungers, a fish pond, grotto and sauna. On an island in the pool is a huge trophy - an apparent nod to the factory's role making food for the country's athletes. This factory claim to be the coolest workplace worldwide.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

A group of workers pose in the swimming pool of the food factory of capital Pyongyang's Mangyongdae district. The fifth floor of a food factory has been turned into a place of fun, the waterpark, complete with pools and basketball hoops, as well as sunloungers, a fish pond, grotto and sauna. On an island in the pool is a huge trophy - an apparent nod to the factory's role making food for the country's athletes. This factory claim to be the coolest workplace worldwide.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

Gwang Chol, Ri Son Gyong pose in front of the monument of the founding of the Workers' Party of Korea

The Monument to Party Founding is a monument in Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea. The monument is rich in symbolism: the hammer, sickle and calligraphy brush symbolize the workers, farmers and intellectuals. The element is 50 meters high to symbolize the 50-year anniversary of the founding of the Workers' Party of Korea. The number of slabs comprising the belt around the monument and its diameter stand for the date of birth of Kim Jong-il. The inscription on the outer belt says "The organizers of the victory of the Korean people and the leader of the Workers Party of Korea!" On the inside of the belt are three bronze reliefs with their distinct meanings: the historical root of the party, the unity of people under the party and the party's vision for a progressive future. Two red flag-shaped buildings with letters forming the words "ever-victorious" surround the monument.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

Gwang Chol, Ri Son Gyong pose in front of the monument of the founding of the Workers' Party of Korea

The Monument to Party Founding is a monument in Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea. The monument is rich in symbolism: the hammer, sickle and calligraphy brush symbolize the workers, farmers and intellectuals. The element is 50 meters high to symbolize the 50-year anniversary of the founding of the Workers' Party of Korea. The number of slabs comprising the belt around the monument and its diameter stand for the date of birth of Kim Jong-il. The inscription on the outer belt says "The organizers of the victory of the Korean people and the leader of the Workers Party of Korea!" On the inside of the belt are three bronze reliefs with their distinct meanings: the historical root of the party, the unity of people under the party and the party's vision for a progressive future. Two red flag-shaped buildings with letters forming the words "ever-victorious" surround the monument.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

A group of children is playing with manual bumpers cars at Mangyondae amusement park.

The amusement park is only 12 kilometers from the north Korean capital city of Pyongyang, boast an area of 700 000 square meters including a repaired rollercoaster, merry-go-round, a train ride and a wading pool.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

A group of children is playing with manual bumpers cars at Mangyondae amusement park.

The amusement park is only 12 kilometers from the north Korean capital city of Pyongyang, boast an area of 700 000 square meters including a repaired rollercoaster, merry-go-round, a train ride and a wading pool.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

A group of children is posing in front of the roller coaster at Mangyondae amusement park.

The amusement park is only 12 kilometers from the north Korean capital city of Pyongyang, boast an area of 700 000 square meters including a repaired rollercoaster, merry-go-round, a train ride and a wading pool.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

A group of children is posing in front of the roller coaster at Mangyondae amusement park.

The amusement park is only 12 kilometers from the north Korean capital city of Pyongyang, boast an area of 700 000 square meters including a repaired rollercoaster, merry-go-round, a train ride and a wading pool.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

Sariwon June 2018

Three workers in a rice field planting rice in Sariwon collective farm

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

Sariwon June 2018

Three workers in a rice field planting rice in Sariwon collective farm

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

Worker of the Zhenghsu Pyongyang textile factory.

Zhengsu Pyongyang textile factory is North Korea's largest textile factory with 8500 workers which 80% of women

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

Worker of the Zhenghsu Pyongyang textile factory.

Zhengsu Pyongyang textile factory is North Korea's largest textile factory with 8500 workers which 80% of women

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

A soldier pose in front of the USS Pueblo, the seizure of a US spy ship by North Korea nearly sparked nuclear war in 1968, 83 US marins were held captive.

Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

A soldier pose in front of the USS Pueblo, the seizure of a US spy ship by North Korea nearly sparked nuclear war in 1968, 83 US marins were held captive.

Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

Sariwon October 2017

Farmer's working in Sariwon Coperative farm

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

Sariwon October 2017

Farmer's working in Sariwon Coperative farm

Otjinene,Namibia- (January 2017) :Herero women from the local community on january 2017 in Otjinene, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Otjinene,Namibia- (January 2017) :Herero women from the local community on january 2017 in Otjinene, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Opuwo,Namibia- (August 2017) :

Kaipatua Kenahama pose in Opuwo on August 2017 in Opuwo, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Opuwo,Namibia- (August 2017) :

Kaipatua Kenahama pose in Opuwo on August 2017 in Opuwo, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Since its appearance in 1950, plastic has conditioned all our daily life. And if at the time nobody was worried about the heap of waste, today humanity is totally addicted to it. Today 13 billion tons of plastic waste are scattered around the world. In 2050 it will be 50 billion tons.

This global problem primarily concerns the poor countries that are becoming the world's garbage cans because the rich countries that are at the origin of their production have them taken over by the poor countries that are becoming the planet's landfills.

Second largest country in Africa, the Democratic Republic of Congo has one of the richest subsoils in the world in gold, coltan, diamonds, cobalt, oil ... and yet remains the 8th poorest country on the planet.

The DRC is a geological scandal.

For decades, like many African countries, Congo Kinshasa has seen its wealth exploited by international companies - mainly Chinese - in a commercial process resembling a new "raw materials syndrome". The lack of commercial equity in the mining and oil sector, the country's increased dependence on China combined with massive corruption by successive governments since decolonization, prohibits any equitable redistribution of the product of natural resources.

The poverty rate affects nearly 65% of the population. Life expectancy at birth is only 48.7 years and the school enrollment rate is 55% for a population of which 60% are under 20 years old.

The Congolese are among the biggest losers of globalization. They very rarely benefit from manufactured products that draw on their country's resources. In general, these products reappear in Africa in the third or fourth generation; at best they are obsolete, but more often than not, they are only waste products from industrialized countries that prefer to relocate their treatment. Kinshasa's slums are very often built on land filled with tons of untreated waste.

"What is born of the earth returns to the earth," Euripides used to say... In the DRC, we have corrupted the virtuous circle by transforming a feeding ground into a garbage can.

Another paradox: from this waste that is burying the slums of Kinshasa has just been born an artistic movement that borrows a lot from the approach of Arte Povera, the protest movement of the consumer society at the end of the 1960s in Italy. It cries out its urgency to live and no longer survive in the garbage and injustice of the world.

Cell phones, plastic, corks, synthetic foam, inner tubes, fabrics, electric cables, syringes, capsule boxes, car parts, cans, everything is raw material - and yet already industrialized! - to denounce the chaos in which the Congo is kept.

Covered with a full mask made from this garbage, a generation of artists rises up and federates in a collective that thirsts for claim, a primary and visceral necessity to create and denounce.

If the Congo has partly lost its animist and mystical traditions, dissolved under the pressure of the Catholicism of the former Belgian colonists, these young artists are returning to the traditional source of the African mask. An inhabited mask, bearer of a spirit, symbol of an overflow.

This collective is "Ndaku, life is beautiful", founded six years ago by the visual artist Eddy Ekete. Today it brings together nearly 25 artists, almost all trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kinshasa.

Since its appearance in 1950, plastic has conditioned all our daily life. And if at the time nobody was worried about the heap of waste, today humanity is totally addicted to it. Today 13 billion tons of plastic waste are scattered around the world. In 2050 it will be 50 billion tons.

This global problem primarily concerns the poor countries that are becoming the world's garbage cans because the rich countries that are at the origin of their production have them taken over by the poor countries that are becoming the planet's landfills.

Second largest country in Africa, the Democratic Republic of Congo has one of the richest subsoils in the world in gold, coltan, diamonds, cobalt, oil ... and yet remains the 8th poorest country on the planet.

The DRC is a geological scandal.

For decades, like many African countries, Congo Kinshasa has seen its wealth exploited by international companies - mainly Chinese - in a commercial process resembling a new "raw materials syndrome". The lack of commercial equity in the mining and oil sector, the country's increased dependence on China combined with massive corruption by successive governments since decolonization, prohibits any equitable redistribution of the product of natural resources.

The poverty rate affects nearly 65% of the population. Life expectancy at birth is only 48.7 years and the school enrollment rate is 55% for a population of which 60% are under 20 years old.

The Congolese are among the biggest losers of globalization. They very rarely benefit from manufactured products that draw on their country's resources. In general, these products reappear in Africa in the third or fourth generation; at best they are obsolete, but more often than not, they are only waste products from industrialized countries that prefer to relocate their treatment. Kinshasa's slums are very often built on land filled with tons of untreated waste.

"What is born of the earth returns to the earth," Euripides used to say... In the DRC, we have corrupted the virtuous circle by transforming a feeding ground into a garbage can.

Another paradox: from this waste that is burying the slums of Kinshasa has just been born an artistic movement that borrows a lot from the approach of Arte Povera, the protest movement of the consumer society at the end of the 1960s in Italy. It cries out its urgency to live and no longer survive in the garbage and injustice of the world.

Cell phones, plastic, corks, synthetic foam, inner tubes, fabrics, electric cables, syringes, capsule boxes, car parts, cans, everything is raw material - and yet already industrialized! - to denounce the chaos in which the Congo is kept.

Covered with a full mask made from this garbage, a generation of artists rises up and federates in a collective that thirsts for claim, a primary and visceral necessity to create and denounce.

If the Congo has partly lost its animist and mystical traditions, dissolved under the pressure of the Catholicism of the former Belgian colonists, these young artists are returning to the traditional source of the African mask. An inhabited mask, bearer of a spirit, symbol of an overflow.

This collective is "Ndaku, life is beautiful", founded six years ago by the visual artist Eddy Ekete. Today it brings together nearly 25 artists, almost all trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kinshasa.

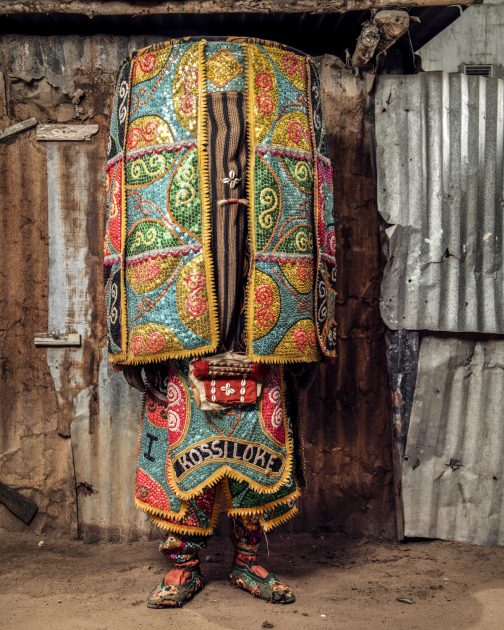

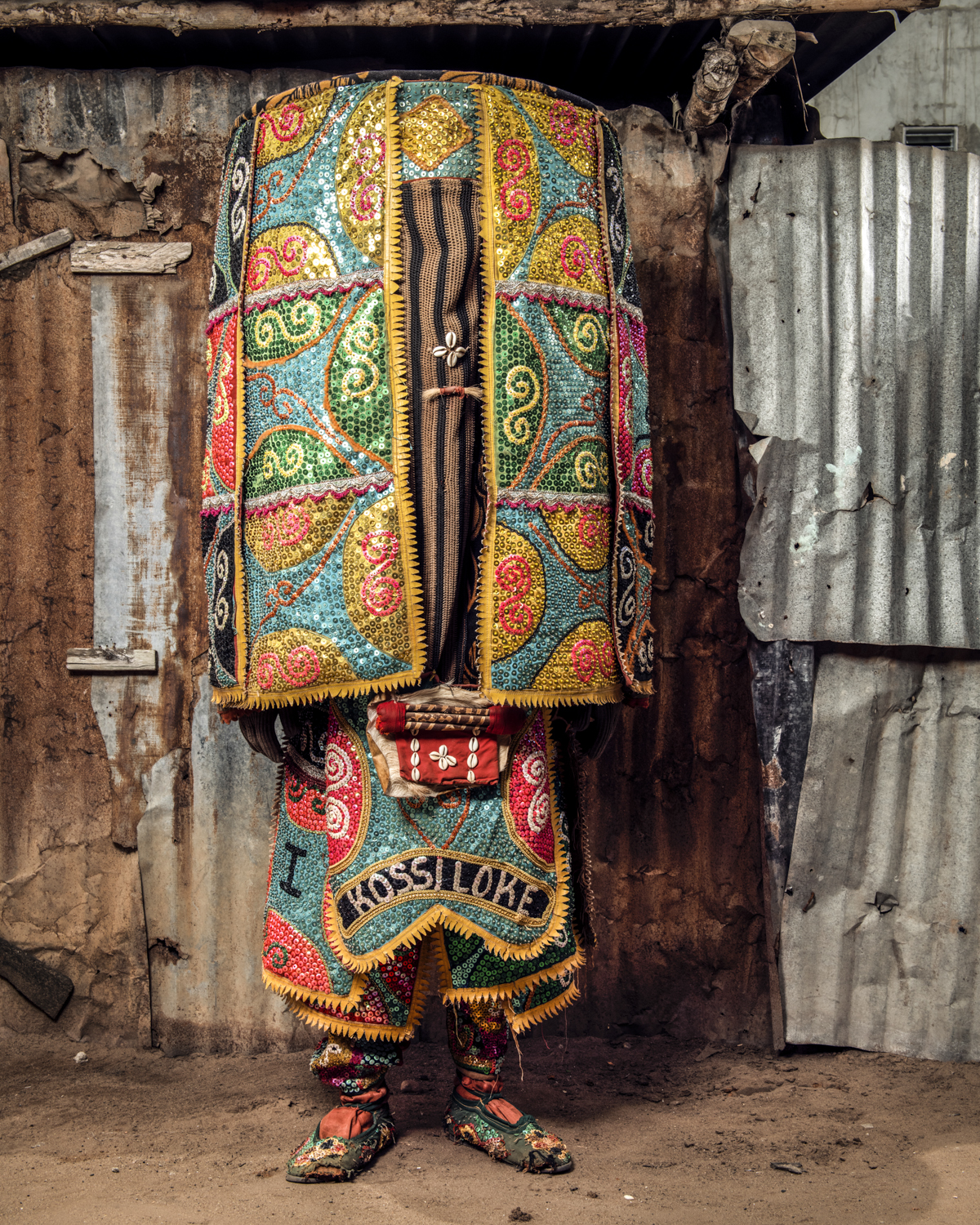

Egungun: Ancestor worship

In Africa, the dead of the family must be honored. For in many African cultures, death does not really exist; the spirit leaves the body to continue its life in the world of the dead, that of the ancestors.

Among the Yoruba, these dead manifest themselves to their descendants through an entity called EGOUN.

It is the spirit of the dead who returns to earth under beautiful loincloths decorated with applications of cut fabric, embroidered and adorned with shells and sequins, bone, and magic wood.

Family and clan societies, strictly reserved for men, have been formed around Egoun the revenant. They evoke the dead, call them and take care of them on earth.

Égoun serves as an intermediary with the souls in the afterlife.

He appears to certain families a few days after the death of one of its members, or during ceremonies performed to honor their memory; he also comes to bring the blessing of the ancestors to the marriages of their descendants and, in certain cases, to welcome a newborn child.

Offerings of food, drink and money are always made to him during his appearances.

EGOUN speaks with a deep, husky voice and dances readily to the sound of Bata or Ogbon drums.

The contact of his loincloth can be fatal to the living, so the MARIWOS (the guardians), members of the EGOUN society, always accompany them, carrying large engraved wooden sticks (lshan) to ward off the unwary. This stick symbolizes the border between the world of the dead (Kou-tome) and the world of the living. Ancestor worship in Africa is directed only to that part of the family that does not go back beyond the founder of the village or the house, that is, to the dynasty of the owners of the inhabited place.

With the exception of the royal families whose members are often deified and therefore have a more important lineage.

This cult is addressed to the deified ancestors and forms a vast system that unites the dead and the living in a continuous and united family whole.

The gods and the dead mix with the living, listen to their complaints, advise them, grant them graces, solve their difficulties and give them remedies for their pains and consolations for their misfortunes. The celestial world is not distant, nor is it superior, and the believer can speak directly with his gods and with his ancestors and benefit from their benevolence.

Each Yoruba clan honors its deceased ancestors in the hope of benefiting from their protection, avoiding their wrath, and keeping the ghosts away from the living.

He therefore regularly brings back the spirit of the ancestors from the realm of the dead (Kou-Tomé)

Each family clan of the ancestor cult has a convent.

It is a sacred place where the masks of the ghosts are kept. It is there that the adepts are trained in secret and that they put on the masks during the ceremonies.

The clan designates those who will be initiated and will have the responsibility of lending their bodies to the spirits of the ancestors and thus, will ensure the dialogue with the ancestors who have become protective deities.

Thus, one or more members of the family are designated, sometimes very young, to be these messengers of the afterlife.

They are taught in secret in a convent for several years, even decades.

There they learn the trance necessary to lend their bodies to the deities, a language that allows them to communicate with the invisible, and to create an appearance...

They emerge from it initiated to the rank of Egungun.

Apart from the initiates, no one knows who is Egungun because during the trances, they appear masked, their bodies totally hidden by their ceremonial costume.

The convent is exclusively reserved for initiates and men, on pain of death. The convent is directed by the Bale, who is generally the head of the family.

The general Alagba is the supreme chief, the king of the Egungun of a city, he watches over the convents of the city.

Egungun: Ancestor worship

In Africa, the dead of the family must be honored. For in many African cultures, death does not really exist; the spirit leaves the body to continue its life in the world of the dead, that of the ancestors.

Among the Yoruba, these dead manifest themselves to their descendants through an entity called EGOUN.

It is the spirit of the dead who returns to earth under beautiful loincloths decorated with applications of cut fabric, embroidered and adorned with shells and sequins, bone, and magic wood.

Family and clan societies, strictly reserved for men, have been formed around Egoun the revenant. They evoke the dead, call them and take care of them on earth.

Égoun serves as an intermediary with the souls in the afterlife.

He appears to certain families a few days after the death of one of its members, or during ceremonies performed to honor their memory; he also comes to bring the blessing of the ancestors to the marriages of their descendants and, in certain cases, to welcome a newborn child.

Offerings of food, drink and money are always made to him during his appearances.

EGOUN speaks with a deep, husky voice and dances readily to the sound of Bata or Ogbon drums.

The contact of his loincloth can be fatal to the living, so the MARIWOS (the guardians), members of the EGOUN society, always accompany them, carrying large engraved wooden sticks (lshan) to ward off the unwary. This stick symbolizes the border between the world of the dead (Kou-tome) and the world of the living. Ancestor worship in Africa is directed only to that part of the family that does not go back beyond the founder of the village or the house, that is, to the dynasty of the owners of the inhabited place.

With the exception of the royal families whose members are often deified and therefore have a more important lineage.

This cult is addressed to the deified ancestors and forms a vast system that unites the dead and the living in a continuous and united family whole.

The gods and the dead mix with the living, listen to their complaints, advise them, grant them graces, solve their difficulties and give them remedies for their pains and consolations for their misfortunes. The celestial world is not distant, nor is it superior, and the believer can speak directly with his gods and with his ancestors and benefit from their benevolence.

Each Yoruba clan honors its deceased ancestors in the hope of benefiting from their protection, avoiding their wrath, and keeping the ghosts away from the living.

He therefore regularly brings back the spirit of the ancestors from the realm of the dead (Kou-Tomé)

Each family clan of the ancestor cult has a convent.

It is a sacred place where the masks of the ghosts are kept. It is there that the adepts are trained in secret and that they put on the masks during the ceremonies.

The clan designates those who will be initiated and will have the responsibility of lending their bodies to the spirits of the ancestors and thus, will ensure the dialogue with the ancestors who have become protective deities.

Thus, one or more members of the family are designated, sometimes very young, to be these messengers of the afterlife.

They are taught in secret in a convent for several years, even decades.

There they learn the trance necessary to lend their bodies to the deities, a language that allows them to communicate with the invisible, and to create an appearance...

They emerge from it initiated to the rank of Egungun.

Apart from the initiates, no one knows who is Egungun because during the trances, they appear masked, their bodies totally hidden by their ceremonial costume.

The convent is exclusively reserved for initiates and men, on pain of death. The convent is directed by the Bale, who is generally the head of the family.

The general Alagba is the supreme chief, the king of the Egungun of a city, he watches over the convents of the city.

Talismanis,Namibia- (January 2017) : Herero communittee in Talismanis on january 2017 in Talismanis, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Talismanis,Namibia- (January 2017) : Herero communittee in Talismanis on january 2017 in Talismanis, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Les Surmas appelé aussi Suri sont des habitants du sud de l'Éthiopie vivant dans la vallée de l'Omo. Les Suris pratiquent des modifications corporelles, telles que les peintures rituelles et le port de labrets chez les femmes. Encouragés dès leur plus jeune âge à imiter les adultes, les enfants Surma s’enduisent le corps et le visage de pâtes calcaires diversement pigmentées suivant la roche utilisée, selon des contours d’une extrême fantaisie. Certains motifs font allusion à la nature ou aux animaux : robes des vaches, faciès des singes colobes, pelage des prédateurs… Lorsque plusieurs personnes se peignent de façon identique, cela signifie qu’ils sont liés familialement ou d’amitié. Ces décorations répondent à un code social bien établi, et il existe diverses façons de se peindre selon le but recherché : séduction ou peintures de guerre devant effrayer l’ennemi. La coiffure est un autre élément prépondérant dans la fierté des guerriers Surma. Ils se rasent le crâne avec des lames de rasoir en laissant quelques lignes décoratives.

La largeur du labret donne une estimation de la dot dont aura à s’acquitter tout prétendant. La dot peut représenter jusqu’à une soixantaine de bêtes. Les labrets en bois peuvent être de forme trapézoïdale ou demi sphérique, tandis que ceux en argile seront généralement ronds. En âge de se marier, la jeune fille Surma, après s’être fait percer sa lèvre et extraire des dents de la mâchoire inférieure, mettra tout en œuvre pour distendre cet orifice en y insérant des labrets successifs, de taille toujours croissante. En général, toutes les filles d’une classe d’âge se font inciser en même temps, et lorsque la coupure pratiquée a cicatrisée, le village célèbre cet événement par une fête nommée Zigroo. On y boit le bordray, sorte de boisson fermentée à base de farines de sorgho et de maïs blanc.

Pour les hommes, il est d’usage de procéder à des scarific

Les Surmas appelé aussi Suri sont des habitants du sud de l'Éthiopie vivant dans la vallée de l'Omo. Les Suris pratiquent des modifications corporelles, telles que les peintures rituelles et le port de labrets chez les femmes. Encouragés dès leur plus jeune âge à imiter les adultes, les enfants Surma s’enduisent le corps et le visage de pâtes calcaires diversement pigmentées suivant la roche utilisée, selon des contours d’une extrême fantaisie. Certains motifs font allusion à la nature ou aux animaux : robes des vaches, faciès des singes colobes, pelage des prédateurs… Lorsque plusieurs personnes se peignent de façon identique, cela signifie qu’ils sont liés familialement ou d’amitié. Ces décorations répondent à un code social bien établi, et il existe diverses façons de se peindre selon le but recherché : séduction ou peintures de guerre devant effrayer l’ennemi. La coiffure est un autre élément prépondérant dans la fierté des guerriers Surma. Ils se rasent le crâne avec des lames de rasoir en laissant quelques lignes décoratives.

La largeur du labret donne une estimation de la dot dont aura à s’acquitter tout prétendant. La dot peut représenter jusqu’à une soixantaine de bêtes. Les labrets en bois peuvent être de forme trapézoïdale ou demi sphérique, tandis que ceux en argile seront généralement ronds. En âge de se marier, la jeune fille Surma, après s’être fait percer sa lèvre et extraire des dents de la mâchoire inférieure, mettra tout en œuvre pour distendre cet orifice en y insérant des labrets successifs, de taille toujours croissante. En général, toutes les filles d’une classe d’âge se font inciser en même temps, et lorsque la coupure pratiquée a cicatrisée, le village célèbre cet événement par une fête nommée Zigroo. On y boit le bordray, sorte de boisson fermentée à base de farines de sorgho et de maïs blanc.

Pour les hommes, il est d’usage de procéder à des scarific

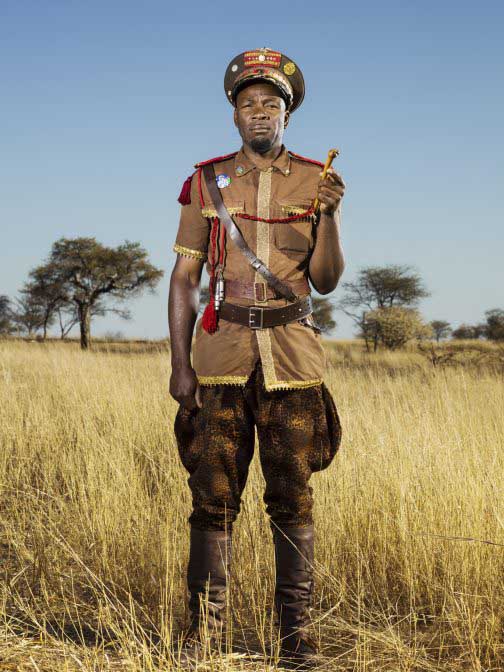

Okahandja,Namibia- (August 2017) :

Uatanaura Handura from Ohondjatu pose in Okahandja.

For the Herero, the ancestor commemoration ceremony are the most commun annual ceremony. The major one take place in Okahandja where most of the famous Herero chief have been buried.

Herero believe in the sacred fire, it's thay to be connected with their ancestor.

For this ceremony everyone get dress with the most amazing uniform, on august 2017 in Okahandja, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Okahandja,Namibia- (August 2017) :

Uatanaura Handura from Ohondjatu pose in Okahandja.

For the Herero, the ancestor commemoration ceremony are the most commun annual ceremony. The major one take place in Okahandja where most of the famous Herero chief have been buried.

Herero believe in the sacred fire, it's thay to be connected with their ancestor.

For this ceremony everyone get dress with the most amazing uniform, on august 2017 in Okahandja, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Otjinaho,Namibia- (January 2017) : Daniel Hangero and his grand daughter Isabella Ktjiremba,Daniel has been driving this Ford for 26 years, on january 2017 in Otjinaho, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Otjinaho,Namibia- (January 2017) : Daniel Hangero and his grand daughter Isabella Ktjiremba,Daniel has been driving this Ford for 26 years, on january 2017 in Otjinaho, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Otjinaho,Namibia- (January 2017) : Aram and Tuemuzunda (in the suit) on january 2017 in Otjinaho, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Otjinaho,Namibia- (January 2017) : Aram and Tuemuzunda (in the suit) on january 2017 in Otjinaho, Namibia. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu)

Les Surmas appelé aussi Suri sont des habitants du sud de l'Éthiopie vivant dans la vallée de l'Omo. Les Suris pratiquent des modifications corporelles, telles que les peintures rituelles et le port de labrets chez les femmes. Encouragés dès leur plus jeune âge à imiter les adultes, les enfants Surma s’enduisent le corps et le visage de pâtes calcaires diversement pigmentées suivant la roche utilisée, selon des contours d’une extrême fantaisie. Certains motifs font allusion à la nature ou aux animaux : robes des vaches, faciès des singes colobes, pelage des prédateurs… Lorsque plusieurs personnes se peignent de façon identique, cela signifie qu’ils sont liés familialement ou d’amitié. Ces décorations répondent à un code social bien établi, et il existe diverses façons de se peindre selon le but recherché : séduction ou peintures de guerre devant effrayer l’ennemi. La coiffure est un autre élément prépondérant dans la fierté des guerriers Surma. Ils se rasent le crâne avec des lames de rasoir en laissant quelques lignes décoratives.

La largeur du labret donne une estimation de la dot dont aura à s’acquitter tout prétendant. La dot peut représenter jusqu’à une soixantaine de bêtes. Les labrets en bois peuvent être de forme trapézoïdale ou demi sphérique, tandis que ceux en argile seront généralement ronds. En âge de se marier, la jeune fille Surma, après s’être fait percer sa lèvre et extraire des dents de la mâchoire inférieure, mettra tout en œuvre pour distendre cet orifice en y insérant des labrets successifs, de taille toujours croissante. En général, toutes les filles d’une classe d’âge se font inciser en même temps, et lorsque la coupure pratiquée a cicatrisée, le village célèbre cet événement par une fête nommée Zigroo. On y boit le bordray, sorte de boisson fermentée à base de farines de sorgho et de maïs blanc.

Pour les hommes, il est d’usage de procéder à des scarific

Les Surmas appelé aussi Suri sont des habitants du sud de l'Éthiopie vivant dans la vallée de l'Omo. Les Suris pratiquent des modifications corporelles, telles que les peintures rituelles et le port de labrets chez les femmes. Encouragés dès leur plus jeune âge à imiter les adultes, les enfants Surma s’enduisent le corps et le visage de pâtes calcaires diversement pigmentées suivant la roche utilisée, selon des contours d’une extrême fantaisie. Certains motifs font allusion à la nature ou aux animaux : robes des vaches, faciès des singes colobes, pelage des prédateurs… Lorsque plusieurs personnes se peignent de façon identique, cela signifie qu’ils sont liés familialement ou d’amitié. Ces décorations répondent à un code social bien établi, et il existe diverses façons de se peindre selon le but recherché : séduction ou peintures de guerre devant effrayer l’ennemi. La coiffure est un autre élément prépondérant dans la fierté des guerriers Surma. Ils se rasent le crâne avec des lames de rasoir en laissant quelques lignes décoratives.

La largeur du labret donne une estimation de la dot dont aura à s’acquitter tout prétendant. La dot peut représenter jusqu’à une soixantaine de bêtes. Les labrets en bois peuvent être de forme trapézoïdale ou demi sphérique, tandis que ceux en argile seront généralement ronds. En âge de se marier, la jeune fille Surma, après s’être fait percer sa lèvre et extraire des dents de la mâchoire inférieure, mettra tout en œuvre pour distendre cet orifice en y insérant des labrets successifs, de taille toujours croissante. En général, toutes les filles d’une classe d’âge se font inciser en même temps, et lorsque la coupure pratiquée a cicatrisée, le village célèbre cet événement par une fête nommée Zigroo. On y boit le bordray, sorte de boisson fermentée à base de farines de sorgho et de maïs blanc.

Pour les hommes, il est d’usage de procéder à des scarific

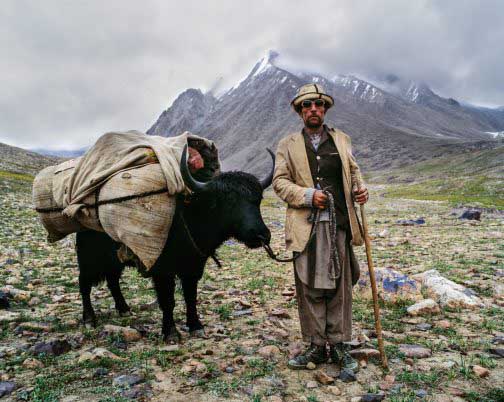

Amou Daria’s valley, Wakhan, AFGHANISTAN - 1998 : (5000 m). 15 August, 6 AM, the first vision of the day, a man with is yack coming from nowhere ,on 1998, in Wakhan, Afghanistan.

Amou Daria’s valley, Wakhan, AFGHANISTAN - 1998 : (5000 m). 15 August, 6 AM, the first vision of the day, a man with is yack coming from nowhere ,on 1998, in Wakhan, Afghanistan.

Les Maï-Maï, ou parfois Mayi-Mayi, est un terme général décrivant des groupes armés actifs au cours de la Deuxième guerre du Congo en République démocratique du Congo (RDC).

Le terme Maï-Maï provient de Maï ou Maji, eau dans les langues bantoues de la région. Il fait référence à la révolte Maji Maji intervenue en 1905-1907 au Tanganyika, lors du mouvement populaire de rébellion contre l'occupant allemand dont les combattants étaient protégés par les propriétés magiques de l'eau.

Les guerriers Maï-Maï se croient invulnérables aux armes à feu. Ils s'aspergent d'une potion magique censée faire couler les balles sur leur corps comme de l'eau (maï en swahili).

La plupart se constituèrent pour résister à l'invasion des forces armées du Rwanda. Ils ont été actifs dans les provinces du Nord-Kivu et du Sud-Kivu.

Bien que les Kivus aient été militarisés de longue date, en particulier parmi les minorités Batembo et Bembes, l'instabilité dans la région amena les habitants à constituer les milices Maï-Maï. Que ce soit en tant que groupe unis ou en tant que groupes individuels.

Les groupes repris sous l'appellation « Maï-Maï » incluent des forces armées dirigées par des seigneurs de guerre, des chefs tribaux traditionnels, des chefs de village, et des dirigeants politiques locaux.

Les Maï-Maï, ou parfois Mayi-Mayi, est un terme général décrivant des groupes armés actifs au cours de la Deuxième guerre du Congo en République démocratique du Congo (RDC).

Le terme Maï-Maï provient de Maï ou Maji, eau dans les langues bantoues de la région. Il fait référence à la révolte Maji Maji intervenue en 1905-1907 au Tanganyika, lors du mouvement populaire de rébellion contre l'occupant allemand dont les combattants étaient protégés par les propriétés magiques de l'eau.

Les guerriers Maï-Maï se croient invulnérables aux armes à feu. Ils s'aspergent d'une potion magique censée faire couler les balles sur leur corps comme de l'eau (maï en swahili).

La plupart se constituèrent pour résister à l'invasion des forces armées du Rwanda. Ils ont été actifs dans les provinces du Nord-Kivu et du Sud-Kivu.

Bien que les Kivus aient été militarisés de longue date, en particulier parmi les minorités Batembo et Bembes, l'instabilité dans la région amena les habitants à constituer les milices Maï-Maï. Que ce soit en tant que groupe unis ou en tant que groupes individuels.

Les groupes repris sous l'appellation « Maï-Maï » incluent des forces armées dirigées par des seigneurs de guerre, des chefs tribaux traditionnels, des chefs de village, et des dirigeants politiques locaux.

Les Maï-Maï, ou parfois Mayi-Mayi, est un terme général décrivant des groupes armés actifs au cours de la Deuxième guerre du Congo en République démocratique du Congo (RDC).

Le terme Maï-Maï provient de Maï ou Maji, eau dans les langues bantoues de la région. Il fait référence à la révolte Maji Maji intervenue en 1905-1907 au Tanganyika, lors du mouvement populaire de rébellion contre l'occupant allemand dont les combattants étaient protégés par les propriétés magiques de l'eau.

Les guerriers Maï-Maï se croient invulnérables aux armes à feu. Ils s'aspergent d'une potion magique censée faire couler les balles sur leur corps comme de l'eau (maï en swahili).

La plupart se constituèrent pour résister à l'invasion des forces armées du Rwanda. Ils ont été actifs dans les provinces du Nord-Kivu et du Sud-Kivu.

Bien que les Kivus aient été militarisés de longue date, en particulier parmi les minorités Batembo et Bembes, l'instabilité dans la région amena les habitants à constituer les milices Maï-Maï. Que ce soit en tant que groupe unis ou en tant que groupes individuels.

Les groupes repris sous l'appellation « Maï-Maï » incluent des forces armées dirigées par des seigneurs de guerre, des chefs tribaux traditionnels, des chefs de village, et des dirigeants politiques locaux.

Les Maï-Maï, ou parfois Mayi-Mayi, est un terme général décrivant des groupes armés actifs au cours de la Deuxième guerre du Congo en République démocratique du Congo (RDC).

Le terme Maï-Maï provient de Maï ou Maji, eau dans les langues bantoues de la région. Il fait référence à la révolte Maji Maji intervenue en 1905-1907 au Tanganyika, lors du mouvement populaire de rébellion contre l'occupant allemand dont les combattants étaient protégés par les propriétés magiques de l'eau.

Les guerriers Maï-Maï se croient invulnérables aux armes à feu. Ils s'aspergent d'une potion magique censée faire couler les balles sur leur corps comme de l'eau (maï en swahili).

La plupart se constituèrent pour résister à l'invasion des forces armées du Rwanda. Ils ont été actifs dans les provinces du Nord-Kivu et du Sud-Kivu.

Bien que les Kivus aient été militarisés de longue date, en particulier parmi les minorités Batembo et Bembes, l'instabilité dans la région amena les habitants à constituer les milices Maï-Maï. Que ce soit en tant que groupe unis ou en tant que groupes individuels.

Les groupes repris sous l'appellation « Maï-Maï » incluent des forces armées dirigées par des seigneurs de guerre, des chefs tribaux traditionnels, des chefs de village, et des dirigeants politiques locaux.

À Boali, les bénéficiaires du Projet Londo exhibent fièrement leurs vélos flambant neufs, bonus qu’ils obtiennent lorsqu’ils décrochent un emploi dans le cadre de ces travaux à haute intensité de main d’œuvre financés par la Banque mondiale.

In Boali, beneficiaries of Project Londo (“Stand Up”) proudly show off their brand-new bicycles, given as a bonus to new hires with the Labor-Intensive Works initiative financed

by the World Bank.

À Boali, les bénéficiaires du Projet Londo exhibent fièrement leurs vélos flambant neufs, bonus qu’ils obtiennent lorsqu’ils décrochent un emploi dans le cadre de ces travaux à haute intensité de main d’œuvre financés par la Banque mondiale.

In Boali, beneficiaries of Project Londo (“Stand Up”) proudly show off their brand-new bicycles, given as a bonus to new hires with the Labor-Intensive Works initiative financed

by the World Bank.

Arielle Agrokannoun (left), a nurse in the health center at Athiémé, a city of 40,000 people 100 kilometers from Cotonou, the capital of Benin, examines an 18-month-old boy whose mother has just given birth to another child. His grandmother (right), Marie Adbassou, 37, holds her own youngest child, age 2. In this health center, malaria is the most common illness among children.

Arielle Agrokannoun (left), a nurse in the health center at Athiémé, a city of 40,000 people 100 kilometers from Cotonou, the capital of Benin, examines an 18-month-old boy whose mother has just given birth to another child. His grandmother (right), Marie Adbassou, 37, holds her own youngest child, age 2. In this health center, malaria is the most common illness among children.

La famille Aquelbec

Aquelbek et Narguiza

Situé à 3000 mètres d'altitude, le lac Song-Kul acceuille les nomades de mai à septembre. Il y laisse paître les troupeaux de vaches, moutons et chevaux, leur principale richesse et la principale source de leur alimentation

La famille Aquelbec

Aquelbek et Narguiza

Situé à 3000 mètres d'altitude, le lac Song-Kul acceuille les nomades de mai à septembre. Il y laisse paître les troupeaux de vaches, moutons et chevaux, leur principale richesse et la principale source de leur alimentation

Les Surmas appelé aussi Suri sont des habitants du sud de l'Éthiopie vivant dans la vallée de l'Omo. Les Suris pratiquent des modifications corporelles, telles que les peintures rituelles et le port de labrets chez les femmes. Encouragés dès leur plus jeune âge à imiter les adultes, les enfants Surma s’enduisent le corps et le visage de pâtes calcaires diversement pigmentées suivant la roche utilisée, selon des contours d’une extrême fantaisie. Certains motifs font allusion à la nature ou aux animaux : robes des vaches, faciès des singes colobes, pelage des prédateurs… Lorsque plusieurs personnes se peignent de façon identique, cela signifie qu’ils sont liés familialement ou d’amitié. Ces décorations répondent à un code social bien établi, et il existe diverses façons de se peindre selon le but recherché : séduction ou peintures de guerre devant effrayer l’ennemi. La coiffure est un autre élément prépondérant dans la fierté des guerriers Surma. Ils se rasent le crâne avec des lames de rasoir en laissant quelques lignes décoratives.

La largeur du labret donne une estimation de la dot dont aura à s’acquitter tout prétendant. La dot peut représenter jusqu’à une soixantaine de bêtes. Les labrets en bois peuvent être de forme trapézoïdale ou demi sphérique, tandis que ceux en argile seront généralement ronds. En âge de se marier, la jeune fille Surma, après s’être fait percer sa lèvre et extraire des dents de la mâchoire inférieure, mettra tout en œuvre pour distendre cet orifice en y insérant des labrets successifs, de taille toujours croissante. En général, toutes les filles d’une classe d’âge se font inciser en même temps, et lorsque la coupure pratiquée a cicatrisée, le village célèbre cet événement par une fête nommée Zigroo. On y boit le bordray, sorte de boisson fermentée à base de farines de sorgho et de maïs blanc.

Pour les hommes, il est d’usage de procéder à des scarific

Les Surmas appelé aussi Suri sont des habitants du sud de l'Éthiopie vivant dans la vallée de l'Omo. Les Suris pratiquent des modifications corporelles, telles que les peintures rituelles et le port de labrets chez les femmes. Encouragés dès leur plus jeune âge à imiter les adultes, les enfants Surma s’enduisent le corps et le visage de pâtes calcaires diversement pigmentées suivant la roche utilisée, selon des contours d’une extrême fantaisie. Certains motifs font allusion à la nature ou aux animaux : robes des vaches, faciès des singes colobes, pelage des prédateurs… Lorsque plusieurs personnes se peignent de façon identique, cela signifie qu’ils sont liés familialement ou d’amitié. Ces décorations répondent à un code social bien établi, et il existe diverses façons de se peindre selon le but recherché : séduction ou peintures de guerre devant effrayer l’ennemi. La coiffure est un autre élément prépondérant dans la fierté des guerriers Surma. Ils se rasent le crâne avec des lames de rasoir en laissant quelques lignes décoratives.

La largeur du labret donne une estimation de la dot dont aura à s’acquitter tout prétendant. La dot peut représenter jusqu’à une soixantaine de bêtes. Les labrets en bois peuvent être de forme trapézoïdale ou demi sphérique, tandis que ceux en argile seront généralement ronds. En âge de se marier, la jeune fille Surma, après s’être fait percer sa lèvre et extraire des dents de la mâchoire inférieure, mettra tout en œuvre pour distendre cet orifice en y insérant des labrets successifs, de taille toujours croissante. En général, toutes les filles d’une classe d’âge se font inciser en même temps, et lorsque la coupure pratiquée a cicatrisée, le village célèbre cet événement par une fête nommée Zigroo. On y boit le bordray, sorte de boisson fermentée à base de farines de sorgho et de maïs blanc.

Pour les hommes, il est d’usage de procéder à des scarific

Octobre 2016

Sur la route une famille revient en ville avec sa yourte apr�s quelques mois pass�s dans les paturages

Kirghizistan

Octobre 2016

Sur la route une famille revient en ville avec sa yourte apr�s quelques mois pass�s dans les paturages

Kirghizistan

Les Surmas appelé aussi Suri sont des habitants du sud de l'Éthiopie vivant dans la vallée de l'Omo. Les Suris pratiquent des modifications corporelles, telles que les peintures rituelles et le port de labrets chez les femmes. Encouragés dès leur plus jeune âge à imiter les adultes, les enfants Surma s’enduisent le corps et le visage de pâtes calcaires diversement pigmentées suivant la roche utilisée, selon des contours d’une extrême fantaisie. Certains motifs font allusion à la nature ou aux animaux : robes des vaches, faciès des singes colobes, pelage des prédateurs… Lorsque plusieurs personnes se peignent de façon identique, cela signifie qu’ils sont liés familialement ou d’amitié. Ces décorations répondent à un code social bien établi, et il existe diverses façons de se peindre selon le but recherché : séduction ou peintures de guerre devant effrayer l’ennemi. La coiffure est un autre élément prépondérant dans la fierté des guerriers Surma. Ils se rasent le crâne avec des lames de rasoir en laissant quelques lignes décoratives.

La largeur du labret donne une estimation de la dot dont aura à s’acquitter tout prétendant. La dot peut représenter jusqu’à une soixantaine de bêtes. Les labrets en bois peuvent être de forme trapézoïdale ou demi sphérique, tandis que ceux en argile seront généralement ronds. En âge de se marier, la jeune fille Surma, après s’être fait percer sa lèvre et extraire des dents de la mâchoire inférieure, mettra tout en œuvre pour distendre cet orifice en y insérant des labrets successifs, de taille toujours croissante. En général, toutes les filles d’une classe d’âge se font inciser en même temps, et lorsque la coupure pratiquée a cicatrisée, le village célèbre cet événement par une fête nommée Zigroo. On y boit le bordray, sorte de boisson fermentée à base de farines de sorgho et de maïs blanc.

Pour les hommes, il est d’usage de procéder à des scarific

Les Surmas appelé aussi Suri sont des habitants du sud de l'Éthiopie vivant dans la vallée de l'Omo. Les Suris pratiquent des modifications corporelles, telles que les peintures rituelles et le port de labrets chez les femmes. Encouragés dès leur plus jeune âge à imiter les adultes, les enfants Surma s’enduisent le corps et le visage de pâtes calcaires diversement pigmentées suivant la roche utilisée, selon des contours d’une extrême fantaisie. Certains motifs font allusion à la nature ou aux animaux : robes des vaches, faciès des singes colobes, pelage des prédateurs… Lorsque plusieurs personnes se peignent de façon identique, cela signifie qu’ils sont liés familialement ou d’amitié. Ces décorations répondent à un code social bien établi, et il existe diverses façons de se peindre selon le but recherché : séduction ou peintures de guerre devant effrayer l’ennemi. La coiffure est un autre élément prépondérant dans la fierté des guerriers Surma. Ils se rasent le crâne avec des lames de rasoir en laissant quelques lignes décoratives.

La largeur du labret donne une estimation de la dot dont aura à s’acquitter tout prétendant. La dot peut représenter jusqu’à une soixantaine de bêtes. Les labrets en bois peuvent être de forme trapézoïdale ou demi sphérique, tandis que ceux en argile seront généralement ronds. En âge de se marier, la jeune fille Surma, après s’être fait percer sa lèvre et extraire des dents de la mâchoire inférieure, mettra tout en œuvre pour distendre cet orifice en y insérant des labrets successifs, de taille toujours croissante. En général, toutes les filles d’une classe d’âge se font inciser en même temps, et lorsque la coupure pratiquée a cicatrisée, le village célèbre cet événement par une fête nommée Zigroo. On y boit le bordray, sorte de boisson fermentée à base de farines de sorgho et de maïs blanc.

Pour les hommes, il est d’usage de procéder à des scarific

Portrait of Ferdinand Gilson, first world war veteran, posing with a portrait of him the day of the mobilisation.

Portrait of Ferdinand Gilson, first world war veteran, posing with a portrait of him the day of the mobilisation.

WORLD WAR II VETERANS

FRANCE/CAEN/MARS 2014

JANINE HARDY, CIVIL NURSE, AT THE EXACT PLACE SHE STARTED TO HELP AFTER THE MASS BOMBING OF CAEN CITY.

JANINE IS STILL LEAVING 100 METERS FAR AWAY FROM THIS STREET.

JANINE HARDY, INFIRMIERE BENEVOLE A L'ENDROIT EXACTE OU ELLE DEVINT INFIRMIERE IL Y A 70 ANS DANS LES RUINES DE CAEN DETRUIT PAR LE BOMBARDEMENT.JANINE HABITE A 100 METRES DE LA;

WORLD WAR II VETERANS

FRANCE/CAEN/MARS 2014

JANINE HARDY, CIVIL NURSE, AT THE EXACT PLACE SHE STARTED TO HELP AFTER THE MASS BOMBING OF CAEN CITY.

JANINE IS STILL LEAVING 100 METERS FAR AWAY FROM THIS STREET.

JANINE HARDY, INFIRMIERE BENEVOLE A L'ENDROIT EXACTE OU ELLE DEVINT INFIRMIERE IL Y A 70 ANS DANS LES RUINES DE CAEN DETRUIT PAR LE BOMBARDEMENT.JANINE HABITE A 100 METRES DE LA;

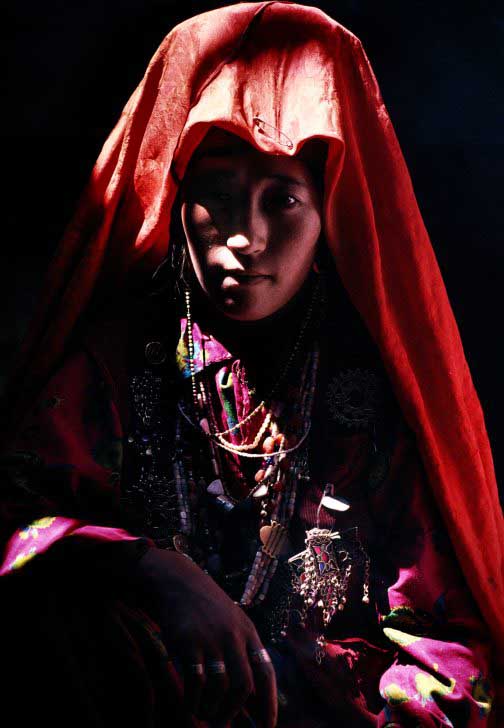

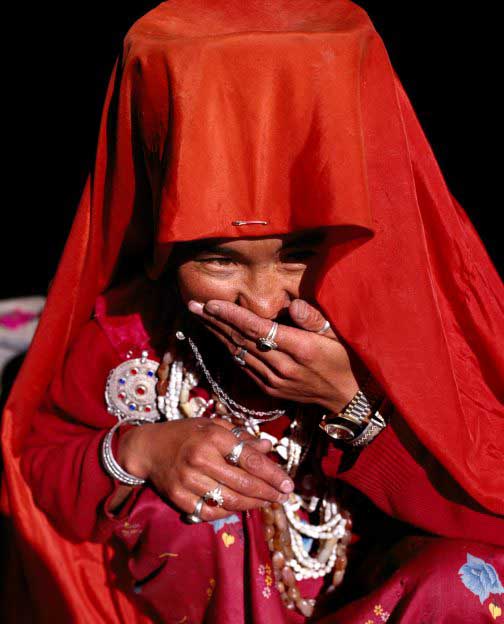

Amou Daria’s valley, Wakhan, AFGHANISTAN - 1998 : (4200 m). Portrait of Aleila, the bây’s daughter,on 1998, in Wakhan, Afghanistan.

Amou Daria’s valley, Wakhan, AFGHANISTAN - 1998 : (4200 m). Portrait of Aleila, the bây’s daughter,on 1998, in Wakhan, Afghanistan.

Amou Daria’s valley, Wakhan, AFGHANISTAN - 1998 : (4200 m). Portrait of Aleila, the bây’s daughter,on 1998, in Wakhan, Afghanistan.

Amou Daria’s valley, Wakhan, AFGHANISTAN - 1998 : (4200 m). Portrait of Aleila, the bây’s daughter,on 1998, in Wakhan, Afghanistan.

Lahe, Myanmar - (january 2013) :Heimi warrior refreshing near Lahe on (january 2013) in Lahe, Myanmar. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu/Getty Images)

Lahe, Myanmar - (january 2013) :Heimi warrior refreshing near Lahe on (january 2013) in Lahe, Myanmar. (Photo by Stephan Gladieu/Getty Images)

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

A family pose in Pyongyang central ZOO

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

A family pose in Pyongyang central ZOO

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

Kim Un Ju ans Ri Sol Hwa at Ryugyong Ophtalmic hospital

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

Kim Un Ju ans Ri Sol Hwa at Ryugyong Ophtalmic hospital

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

Ra Yung Jong, saler of lingerie pose in the workshop of the Zhenghsu Pyongyang textile factory.

Zhengsu Pyongyang textile factory is North Korea's largest textile factory with 8500 workers which 80% of women

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

Ra Yung Jong, saler of lingerie pose in the workshop of the Zhenghsu Pyongyang textile factory.

Zhengsu Pyongyang textile factory is North Korea's largest textile factory with 8500 workers which 80% of women

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

O Yong Ae, a traffic woman pose in the center of Pyongyang.

The are chosen for their looks in a society that still remains mainly traditionalist.

The women must leave the role if they marry, and have a finite shelf-life, with compulsory retirement looming at just 26.

The traffic ladies were originally introduced in the 1980s, when vehicles were a rarity on the streets of Pyongyang and remained so for decades, giving rise to the surreal sight of them directing - with precision and energy - non-existent cars on wide but deserted boulevards.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

O Yong Ae, a traffic woman pose in the center of Pyongyang.

The are chosen for their looks in a society that still remains mainly traditionalist.

The women must leave the role if they marry, and have a finite shelf-life, with compulsory retirement looming at just 26.

The traffic ladies were originally introduced in the 1980s, when vehicles were a rarity on the streets of Pyongyang and remained so for decades, giving rise to the surreal sight of them directing - with precision and energy - non-existent cars on wide but deserted boulevards.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

A man pos in front of a military propaganda poster in Pyongyang central street.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

A man pos in front of a military propaganda poster in Pyongyang central street.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2018

A pastor pose with congregants in Pyongyang protestant temple

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2018

A pastor pose with congregants in Pyongyang protestant temple

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

Four student pose during a break at Kim Il Sung University.

Built in 1946 it's the first and most famous North Korean university

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang June 2017

Four student pose during a break at Kim Il Sung University.

Built in 1946 it's the first and most famous North Korean university

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017

A class room in Pyongyang No. 1 Senior-middle School.

As part of the special education policy for the talented, the North Korean government established Pyongyang No. 1 Senior-middle School in 1984, where education courses correspond with the national curriculum for high schools in South Korea. By 1985, the North Korean regime had established a No.1 Senior-middle School for each provincial government and started a full-scale special education program for the gifted. Located in the Shinwon-dong of Bontongkang-district, Pyongyang, Pyongyang No. 1 Senior-middle School has a total floor space of 28,000 square meters, a four-story building for primary school, a ten-story building for Senior-middle school, dormitories, a cafeteria, and other accessory buildings. It is surely the best school in North Korea.

North Koreans Portraits

North Korea

PyongYang October 2017