Arielle Agrokannoun (left), a nurse in the health center at Athiémé, a city of 40,000 people 100 kilometers from Cotonou, the capital of Benin, examines an 18-month-old boy whose mother has just given birth to another child. His grandmother (right), Marie Adbassou, 37, holds her own youngest child, age 2. In this health center, malaria is the most common illness among children.

Arielle Agrokannoun (left), a nurse in the health center at Athiémé, a city of 40,000 people 100 kilometers from Cotonou, the capital of Benin, examines an 18-month-old boy whose mother has just given birth to another child. His grandmother (right), Marie Adbassou, 37, holds her own youngest child, age 2. In this health center, malaria is the most common illness among children.

In the Bé-Ablogamé district of Lomé, women in the Délali Association have come together under the leadership of Colette Desseh, the wife of the neighbordhood's chief, to back each other up and help their small, home-grown businesses thrive. Colette herself has taken in a bevy of street children, whom she lodges in one of the houses shes owns. Some of her young charges are stunted in growth due to malnutrition.The Déléli Association proclaims in its statutes that " humanitty cannot be happy without addressing the needs of the disadvantaged, especially orphans, children and women.

In the Bé-Ablogamé district of Lomé, women in the Délali Association have come together under the leadership of Colette Desseh, the wife of the neighbordhood's chief, to back each other up and help their small, home-grown businesses thrive. Colette herself has taken in a bevy of street children, whom she lodges in one of the houses shes owns. Some of her young charges are stunted in growth due to malnutrition.The Déléli Association proclaims in its statutes that " humanitty cannot be happy without addressing the needs of the disadvantaged, especially orphans, children and women.

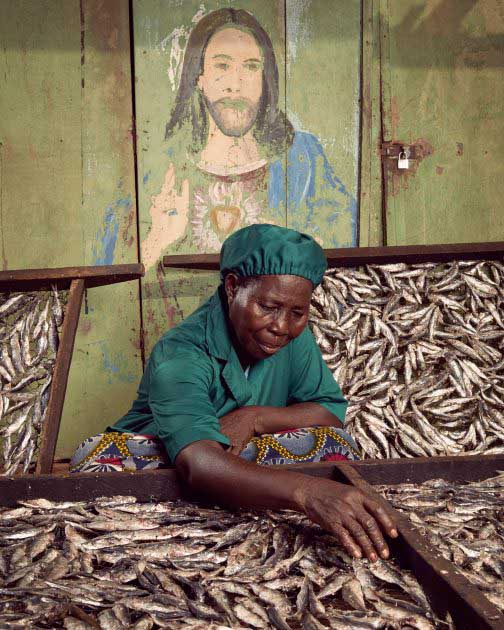

In Togo, 80 percent of the fish that is eaten is smoked over charcoal, a procedure extremely harmful to health. Thanks to support from the World Bank, the women who smoke fish in Katanga, a fishing village near the port of Lomé, Togo capital, now have a modern processing device that allows them to cure the fish without damaging their health. The new method filters out the smoke and produces better-quality fish. Traditional curing generated large amounts of smoke and led to eye and lung diseases in many of the processors (largely women). The traditional smoking technique also posed a danger to the consumer from the harmful particles deposited on the fish. It remains to be seen whether the Togolese, who love smoked fish but are used to the dark color imbued by the customary smoking method, will go for the healthier option.

In Togo, 80 percent of the fish that is eaten is smoked over charcoal, a procedure extremely harmful to health. Thanks to support from the World Bank, the women who smoke fish in Katanga, a fishing village near the port of Lomé, Togo capital, now have a modern processing device that allows them to cure the fish without damaging their health. The new method filters out the smoke and produces better-quality fish. Traditional curing generated large amounts of smoke and led to eye and lung diseases in many of the processors (largely women). The traditional smoking technique also posed a danger to the consumer from the harmful particles deposited on the fish. It remains to be seen whether the Togolese, who love smoked fish but are used to the dark color imbued by the customary smoking method, will go for the healthier option.

Margaret Proise (in blue and pink) runs the Alpha & Omega Beauty Salon in the Gazaland Mall in downtown Kampala. The 35-year-old mother of five is proud her oldest child is about to graduate with a diploma in engineering. Her ambition: to have her own beauty school.

Margaret Proise (in blue and pink) runs the Alpha & Omega Beauty Salon in the Gazaland Mall in downtown Kampala. The 35-year-old mother of five is proud her oldest child is about to graduate with a diploma in engineering. Her ambition: to have her own beauty school.

Rabbit farmer Juliet Atushabe in Kikaaya, a northern suburb of Kampala, Uganda.

Rabbit farmer Juliet Atushabe in Kikaaya, a northern suburb of Kampala, Uganda.

The women still water their plot with watering cans.

Left alone by their husbands, who abandoned Niger’s arid land in search of a better life in neighboring coastal countries, women in the CERNAFA cooperative, in the Tillaberi region of Niger, joined forces 14 years ago to combat malaria, which was devastating their families, to shrink school dropout rates, and to build up their income by growing market crops. Established in 2002, the group began with 52 members and today counts 257. It has become a case study for women’s advancement in Niger.

Each producer farms her own plot (an area of 429 square meters on average), but the women combine their resources to buy equipment. Every year, 10 percent of each woman’s production is remitted to the co-op to finance plans for the future.

The women still water their plot with watering cans.

Left alone by their husbands, who abandoned Niger’s arid land in search of a better life in neighboring coastal countries, women in the CERNAFA cooperative, in the Tillaberi region of Niger, joined forces 14 years ago to combat malaria, which was devastating their families, to shrink school dropout rates, and to build up their income by growing market crops. Established in 2002, the group began with 52 members and today counts 257. It has become a case study for women’s advancement in Niger.

Each producer farms her own plot (an area of 429 square meters on average), but the women combine their resources to buy equipment. Every year, 10 percent of each woman’s production is remitted to the co-op to finance plans for the future.

Nawtonyi Nakyerwa in Mukoko village in central Uganda.

Nawtonyi Nakyerwa in Mukoko village in central Uganda.

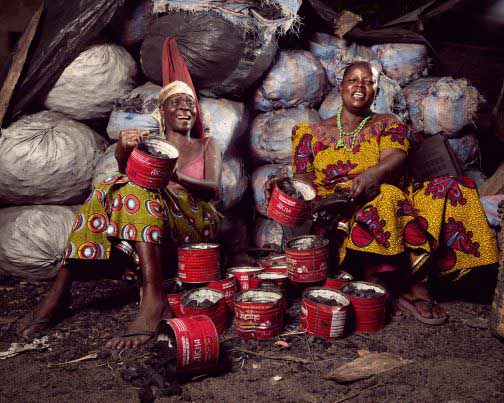

Atatti Ayawovi, 56, and Loumonvi Afi, 60, sell charcoal in the streets of Bè-Ablogam, a rundown neighborhood in the port district of Lomé, the capital of Togo. Although harmful to health, charcoal is the standard household fuel in Togo, as in most countries in Africa. The two are members of the Délali Association, a mutual aid network organized by Colette Desseh, the wife of the traditional chief.

Atatti Ayawovi, 56, and Loumonvi Afi, 60, sell charcoal in the streets of Bè-Ablogam, a rundown neighborhood in the port district of Lomé, the capital of Togo. Although harmful to health, charcoal is the standard household fuel in Togo, as in most countries in Africa. The two are members of the Délali Association, a mutual aid network organized by Colette Desseh, the wife of the traditional chief.

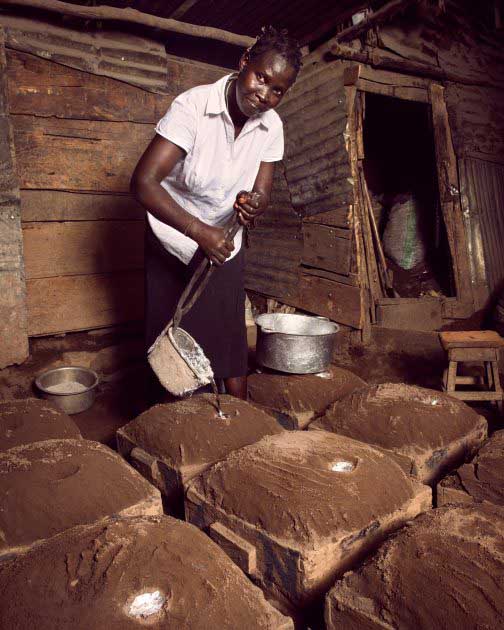

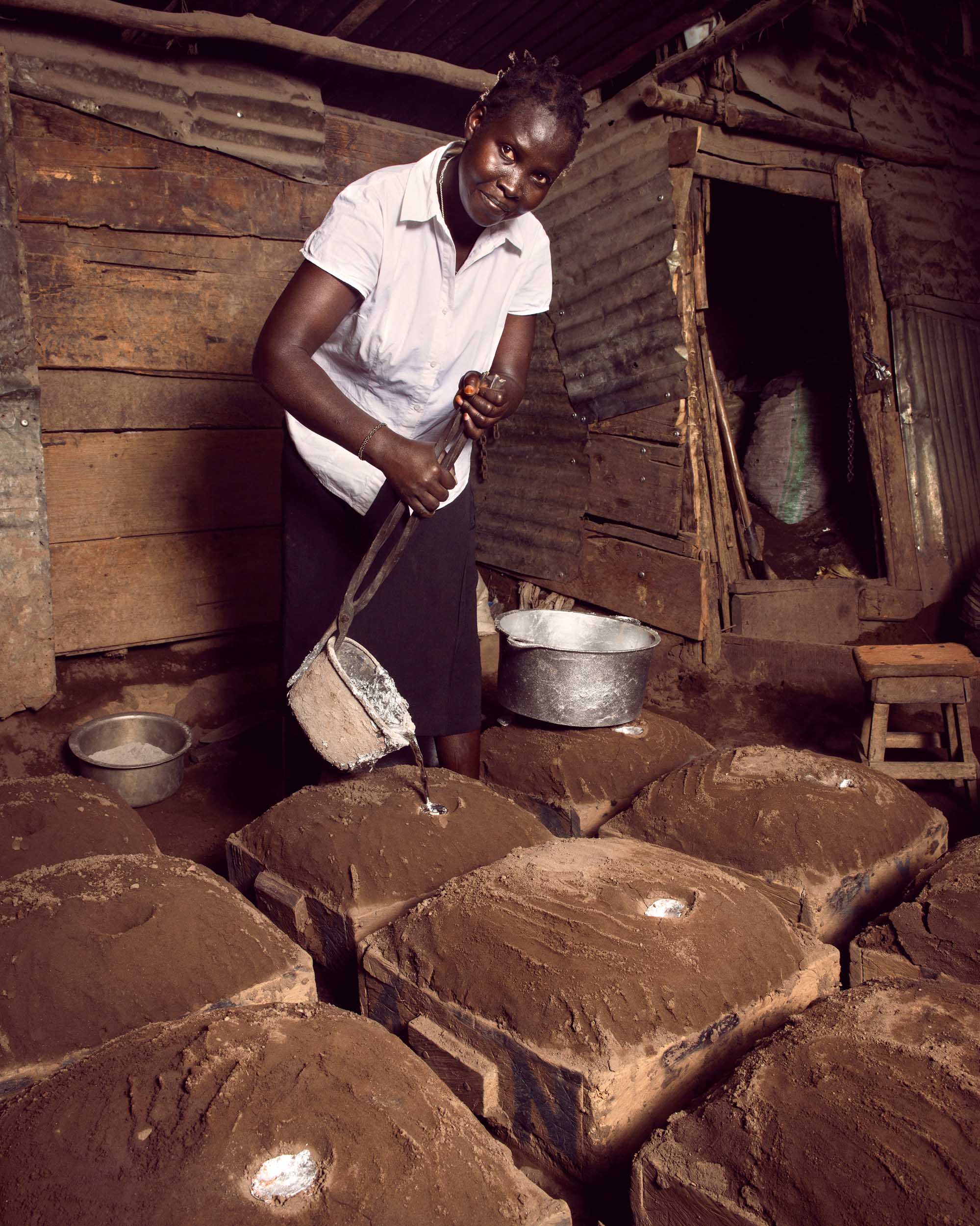

Betty Ajio, 43, pours molten metal into dirt-covered molds to make cooking pots in the Kisenyi slum of Kampala, Uganda. She makes 120 to 230 pots a day as part of a sweltering, open-air production line. Preparing the molds requires a lot of shoveling, and this physically demanding work is typically done by men, but Ajio is not the only woman working here. A metal fabricator for 23 years, she was encouraged by her father to get into the business to improve her earning potential. Today, the mother of seven has four employees and makes enough money to support a nine-person household and pay school fees. She says she would not trade this work for an easier but lower-paying job, and believes other women should learn the trade.

Betty Ajio, 43, pours molten metal into dirt-covered molds to make cooking pots in the Kisenyi slum of Kampala, Uganda. She makes 120 to 230 pots a day as part of a sweltering, open-air production line. Preparing the molds requires a lot of shoveling, and this physically demanding work is typically done by men, but Ajio is not the only woman working here. A metal fabricator for 23 years, she was encouraged by her father to get into the business to improve her earning potential. Today, the mother of seven has four employees and makes enough money to support a nine-person household and pay school fees. She says she would not trade this work for an easier but lower-paying job, and believes other women should learn the trade.

Olivia Nankindu, 27, surveys the fruits of her labor in the waning afternoon sunlight on her farm near Kyotera, Uganda. The mother of two children, aged 4 and 10 months, shared some of her hopes for the future: She wants to be successful and influential in her community. She wants her children to get a good education. She says she thinks she could be good at business, and she dreams of visiting the financial city of New York, and becoming an accountant. She's confident there will be time to pursue her goals. For now, she and her husband farm their land and look forward to a future when they can afford a solar panel and a smart phone. Nankindu says women of her generation need to get involved and take charge of their own destiny -and they can also be leaders.

Olivia Nankindu, 27, surveys the fruits of her labor in the waning afternoon sunlight on her farm near Kyotera, Uganda. The mother of two children, aged 4 and 10 months, shared some of her hopes for the future: She wants to be successful and influential in her community. She wants her children to get a good education. She says she thinks she could be good at business, and she dreams of visiting the financial city of New York, and becoming an accountant. She's confident there will be time to pursue her goals. For now, she and her husband farm their land and look forward to a future when they can afford a solar panel and a smart phone. Nankindu says women of her generation need to get involved and take charge of their own destiny -and they can also be leaders.

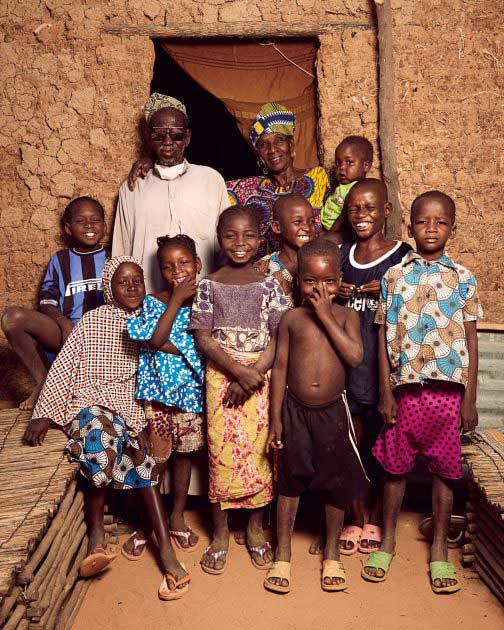

Soumana Kelessi, who wears oversized sunglasses, poses next to his sister Hadjo Kelessi. They live in Kosseye Satom, a village15 kilometers from Niamey, the capital of Niger, consisting of small, mud-brick homes packed with numerous family members. They are surrounded by a bevy of children. Niger's fertility rate, 7.6 children per woman, is the highest in sub-Saharan Africa.

Soumana Kelessi, who wears oversized sunglasses, poses next to his sister Hadjo Kelessi. They live in Kosseye Satom, a village15 kilometers from Niamey, the capital of Niger, consisting of small, mud-brick homes packed with numerous family members. They are surrounded by a bevy of children. Niger's fertility rate, 7.6 children per woman, is the highest in sub-Saharan Africa.

With a bundle of millet on her head, Abou Fumarou Mahamadou poses amid millet stalks dried in the sun. She belongs to a co-op of 32 women farmers in the commune of Tibiri in southwest Niger. The most widely grown grain in Niger, millet is one of the country's dietary mainstays, along with corn, black-eyed peas and rice. The women also grow cabbage, lettuce, tomatoes, potatoes, eggplant and chili peppers. The excess harvest is sold locally as well as in Dosso, the nearest village, and in Niamey, the capital. This year the women sold 90 baskets of tomatoes during the rainy season; the potato crop, on the other hand, was disastrous. And why? The seed had not been ordered at the right time, so it arrived late in the planting season. The same occurred with the onion crop. The majority of women in the group cannot read. She hope to set up a literacy program, but the main hardship for these women is their backbreaking work, Oumarou Farouk, the group leader, says sadly.

With a bundle of millet on her head, Abou Fumarou Mahamadou poses amid millet stalks dried in the sun. She belongs to a co-op of 32 women farmers in the commune of Tibiri in southwest Niger. The most widely grown grain in Niger, millet is one of the country's dietary mainstays, along with corn, black-eyed peas and rice. The women also grow cabbage, lettuce, tomatoes, potatoes, eggplant and chili peppers. The excess harvest is sold locally as well as in Dosso, the nearest village, and in Niamey, the capital. This year the women sold 90 baskets of tomatoes during the rainy season; the potato crop, on the other hand, was disastrous. And why? The seed had not been ordered at the right time, so it arrived late in the planting season. The same occurred with the onion crop. The majority of women in the group cannot read. She hope to set up a literacy program, but the main hardship for these women is their backbreaking work, Oumarou Farouk, the group leader, says sadly.

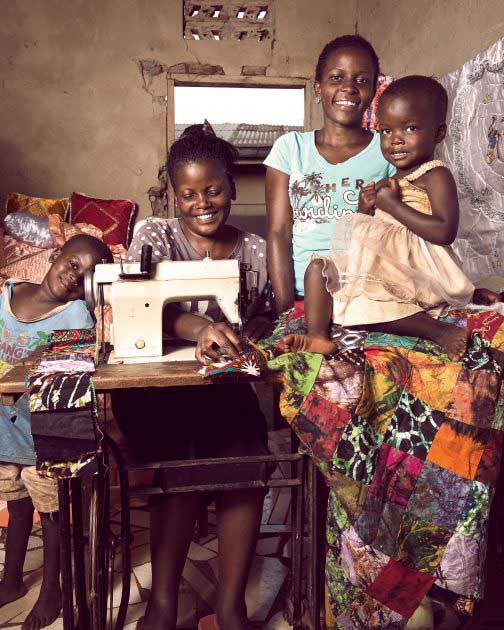

Jessica, 30, and Elizabeth Nawkumba, 20, have a fledgling textiles business in the Kisaasi neighborhood in Kampala, Uganda. The sisters sell baby clothes, bedspreads, and other products made of colorful cloth. They started their business with a 300,000 shilling ($100) loan through a microfinance group at the Kikaaya girls club run by the non-governmental organization, BRAC. They hope someday to have their own shop in Kampala, and maybe beyond. I have a passion for travelling,said Elizabeth. Iwant to go everywhere with my stuff, I want the whole world to know about the things we do because it beautiful.

Jessica, 30, and Elizabeth Nawkumba, 20, have a fledgling textiles business in the Kisaasi neighborhood in Kampala, Uganda. The sisters sell baby clothes, bedspreads, and other products made of colorful cloth. They started their business with a 300,000 shilling ($100) loan through a microfinance group at the Kikaaya girls club run by the non-governmental organization, BRAC. They hope someday to have their own shop in Kampala, and maybe beyond. I have a passion for travelling,said Elizabeth. Iwant to go everywhere with my stuff, I want the whole world to know about the things we do because it beautiful.

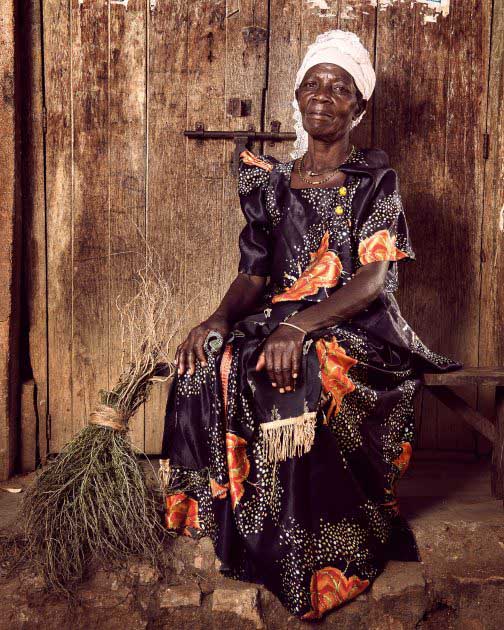

Cecile Dosseh, 60, runs a makeshift grocery in the streets of Bé-Ablogam, a rundown neighborhood in the port district of Lomé, the capital of Togo. The local children love her candy, but times are hard. Cécile is a member of the Délali Association, in which some 30 women come together to back each other up, make their voices heard, and help their small, home-grown businesses thrive. Some, however, such as Cecile, still have a hard time making ends meet.

Cecile Dosseh, 60, runs a makeshift grocery in the streets of Bé-Ablogam, a rundown neighborhood in the port district of Lomé, the capital of Togo. The local children love her candy, but times are hard. Cécile is a member of the Délali Association, in which some 30 women come together to back each other up, make their voices heard, and help their small, home-grown businesses thrive. Some, however, such as Cecile, still have a hard time making ends meet.

Agnes Kivumbi, 45, is surrounded by small children in a dusty courtyard in Lusango Village, in Kalunga, Uganda. The farmer and business owner is teaching mothers about good health and nutrition, and trying to save women's lives along the way. Kivumbi is a community health promoter, earning a small stipend for going from house to house to weigh and measure toddlers and babies. She says about 7% of the children she sees are wasted, meaning they suffer acute malnutrition. She tells their parents to seek help from a health center. She also refers pregnant women to health centers so they can give birth with health professionals, rather than at home, and believes that in doing so she has helped prevent maternal deaths.

Agnes Kivumbi, 45, is surrounded by small children in a dusty courtyard in Lusango Village, in Kalunga, Uganda. The farmer and business owner is teaching mothers about good health and nutrition, and trying to save women's lives along the way. Kivumbi is a community health promoter, earning a small stipend for going from house to house to weigh and measure toddlers and babies. She says about 7% of the children she sees are wasted, meaning they suffer acute malnutrition. She tells their parents to seek help from a health center. She also refers pregnant women to health centers so they can give birth with health professionals, rather than at home, and believes that in doing so she has helped prevent maternal deaths.

Teddy Nakayiwa, 42, and her young daughter at their home in Kantuule, Uganda. Nakayiwa is participating in a project to help women in Uganda unleash the power of the orange-fleshed sweet potato and other bio-fortified crops to fight child malnutrition. The non-native crop is high in beta carotene; as little as 50 grams a day supplies a child's vitamin A needs. The vegetable was introduced to female farmers in the central and southwestern regions of the country in 2014 by the Uganda branch of the Bangladesh-based nongovernmental organization BRAC. A network of women raise the sweet potato, teach others how to grow it, tell communities about nutrition, and monitor the health of children under 2. The effort takes aim at chronic under-nutrition and stunting that affects 33% of children nationally. In June 2015, women in the program said they were empowered by their new-found knowledge and the project modest monetary incentives, and gratified by the impact they had on their communities.

Teddy Nakayiwa, 42, and her young daughter at their home in Kantuule, Uganda. Nakayiwa is participating in a project to help women in Uganda unleash the power of the orange-fleshed sweet potato and other bio-fortified crops to fight child malnutrition. The non-native crop is high in beta carotene; as little as 50 grams a day supplies a child's vitamin A needs. The vegetable was introduced to female farmers in the central and southwestern regions of the country in 2014 by the Uganda branch of the Bangladesh-based nongovernmental organization BRAC. A network of women raise the sweet potato, teach others how to grow it, tell communities about nutrition, and monitor the health of children under 2. The effort takes aim at chronic under-nutrition and stunting that affects 33% of children nationally. In June 2015, women in the program said they were empowered by their new-found knowledge and the project modest monetary incentives, and gratified by the impact they had on their communities.

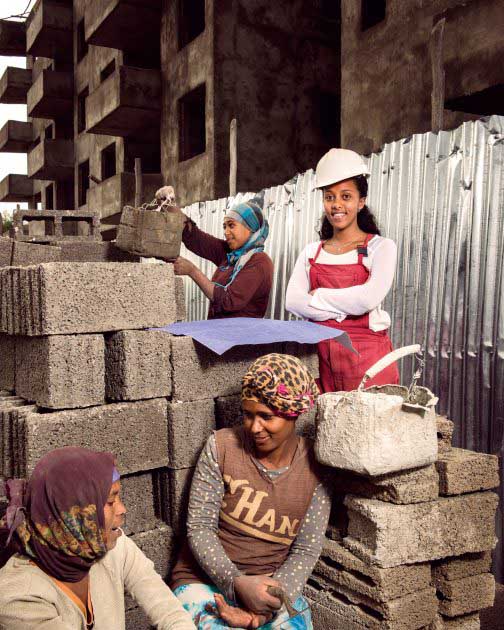

Merharriet Hailemariam, 26, studied to be a journalist, but today she is an electrician working at a 200-acre condominium development 45 minutes from downtown Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Merharriet switched professions when learned she could earn more money as an electrician, and convinced two sisters and two friends to follow her example. She now would like to get a degree in construction technology and management. Working as an entrepreneur is much better than being an employee of an organization, says Merharriet. She adds that there is a lot of opportunity for women in construction, though few women work in the field. Many people think the construction sector is only for men, but women can install electricity as well as any man, she says.

Merharriet Hailemariam, 26, studied to be a journalist, but today she is an electrician working at a 200-acre condominium development 45 minutes from downtown Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Merharriet switched professions when learned she could earn more money as an electrician, and convinced two sisters and two friends to follow her example. She now would like to get a degree in construction technology and management. Working as an entrepreneur is much better than being an employee of an organization, says Merharriet. She adds that there is a lot of opportunity for women in construction, though few women work in the field. Many people think the construction sector is only for men, but women can install electricity as well as any man, she says.

Benin. December 2015. Blanche Waouwa (right), 41, and Pulchérie Oza, 57, are midwives at a hospital in the Lokossa commune of southwest Benin, 200 kilometers from the capital, Cotonou. The hospital’s dilapidated facilities handle birth after birth: Benin’s fertility rate was 4.8 children per woman in 2013. Gynecologist Solange Houedjissin heads the obstetrics department at the hospital, which receives subsidies tied to the quality and quantity of services delivered to patients. “Pregnant women often come here in terrible shape, because so many of them have no sense of the importance of prenatal care,” she says. “And it’s important to educate them about the fact that when there are complications, a caesarean is not inevitable , some women flatly refuse to get into the ambulance to go to the hospital,” she adds. Since 2009, caesareans have been free in Benin, but some hospitals try to make patients pay CFAF 30,000 to 50,000 for “incidental expenses.”

The rate of childbirth by caesarean in this hospital is 27.8 percent (554 out of 1,989 births). In Benin, with help from the World Bank, the Ministry of Health provides financing to health centers based on their results, aiming to improve the quality and quantity of the care they administer. Thanks to the results-based financing (RBF) approach, notable improvements in the quality of care were recorded in all the establishments the program covered. For example, the rate of standard-quality prenatal visits topped 30 percent (compared to 5 percent in the reference year, 2010, and surpassing the program’s target rate, 25 percent).

One of the most significant challenges is to reduce the still inordinately high rate of maternal deaths in childbirth. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), maternal mortality is decreasing very slowly in Benin, from 497 per 100,000 births in 1996 to 350 per 100,000 in 2012, even though many more births take place in the presence of qualified health care providers

Benin. December 2015. Blanche Waouwa (right), 41, and Pulchérie Oza, 57, are midwives at a hospital in the Lokossa commune of southwest Benin, 200 kilometers from the capital, Cotonou. The hospital’s dilapidated facilities handle birth after birth: Benin’s fertility rate was 4.8 children per woman in 2013. Gynecologist Solange Houedjissin heads the obstetrics department at the hospital, which receives subsidies tied to the quality and quantity of services delivered to patients. “Pregnant women often come here in terrible shape, because so many of them have no sense of the importance of prenatal care,” she says. “And it’s important to educate them about the fact that when there are complications, a caesarean is not inevitable , some women flatly refuse to get into the ambulance to go to the hospital,” she adds. Since 2009, caesareans have been free in Benin, but some hospitals try to make patients pay CFAF 30,000 to 50,000 for “incidental expenses.”

The rate of childbirth by caesarean in this hospital is 27.8 percent (554 out of 1,989 births). In Benin, with help from the World Bank, the Ministry of Health provides financing to health centers based on their results, aiming to improve the quality and quantity of the care they administer. Thanks to the results-based financing (RBF) approach, notable improvements in the quality of care were recorded in all the establishments the program covered. For example, the rate of standard-quality prenatal visits topped 30 percent (compared to 5 percent in the reference year, 2010, and surpassing the program’s target rate, 25 percent).

One of the most significant challenges is to reduce the still inordinately high rate of maternal deaths in childbirth. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), maternal mortality is decreasing very slowly in Benin, from 497 per 100,000 births in 1996 to 350 per 100,000 in 2012, even though many more births take place in the presence of qualified health care providers

A cool breeze rustles the matooke leaves atop a picturesque plateau near Kyotera, Uganda. Latifa Nasansa, 42, proudly wears a shimmering green Gomesi -traditional dress for women in Uganda. The mother of three has never married, and is the owner-caretaker of her family's 20-acre farm in Rakai District. People in the community -even men, she says -come to pick a leaf, from her (learn from her example). Lately, she uses her influence to encourage farmers to grow the orange-fleshed sweet potato -a vitamin A-rich food good for young children and elderly people with dimming eyesight. Reflecting on women's position in society, Nasansa says life holds more possibilities today than a decade ago. Women don'thave to depend on husbands to survive--they can get training, learn new things, and start businesses without any man being involved, she says.

A cool breeze rustles the matooke leaves atop a picturesque plateau near Kyotera, Uganda. Latifa Nasansa, 42, proudly wears a shimmering green Gomesi -traditional dress for women in Uganda. The mother of three has never married, and is the owner-caretaker of her family's 20-acre farm in Rakai District. People in the community -even men, she says -come to pick a leaf, from her (learn from her example). Lately, she uses her influence to encourage farmers to grow the orange-fleshed sweet potato -a vitamin A-rich food good for young children and elderly people with dimming eyesight. Reflecting on women's position in society, Nasansa says life holds more possibilities today than a decade ago. Women don'thave to depend on husbands to survive--they can get training, learn new things, and start businesses without any man being involved, she says.

When Sewasew Hailu was a little girl, her grandmother taught her how to do handicrafts. That first experience sparked a lifelong interest and a profession. Today, Sewasew is a clothes designer and part of a growing fashion industry in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. She has built her business over the last seven years and won customers locally, from Europe and other African countries for her wedding dresses, suits, dinner and graduation dresses. All are handmade by Sewasew and five employees in her Addis Ababa shop. Sewasew� challenges include being a single mother of three following a divorce. Obtaining financing has also not easy and is the biggest challenge for anyone starting a business, because of the need for collateral, she says.

When Sewasew Hailu was a little girl, her grandmother taught her how to do handicrafts. That first experience sparked a lifelong interest and a profession. Today, Sewasew is a clothes designer and part of a growing fashion industry in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. She has built her business over the last seven years and won customers locally, from Europe and other African countries for her wedding dresses, suits, dinner and graduation dresses. All are handmade by Sewasew and five employees in her Addis Ababa shop. Sewasew� challenges include being a single mother of three following a divorce. Obtaining financing has also not easy and is the biggest challenge for anyone starting a business, because of the need for collateral, she says.

Antoinette Sossa Epse Adoco, 56, a nurse at a health center in Athiémé, a city in southwest Benin, examines a newborn beside the proud mother, Matilde Tchito. Matilde is 20 years old, and this is her second child. Since 2012, the center has received subsidies based on the quality of care it administers (in a results-based financing program). Before, only 28 percent of residents came to see us. Today, it's up to 49 or 59 percent,says Antoinette. "People are coming to the center because our reception is better, along with our care, and we also do follow-up. Before, we didn't ask patients for their phone number or address. Now we call them if they miss an appointment," sshe explains.

Antoinette Sossa Epse Adoco, 56, a nurse at a health center in Athiémé, a city in southwest Benin, examines a newborn beside the proud mother, Matilde Tchito. Matilde is 20 years old, and this is her second child. Since 2012, the center has received subsidies based on the quality of care it administers (in a results-based financing program). Before, only 28 percent of residents came to see us. Today, it's up to 49 or 59 percent,says Antoinette. "People are coming to the center because our reception is better, along with our care, and we also do follow-up. Before, we didn't ask patients for their phone number or address. Now we call them if they miss an appointment," sshe explains.

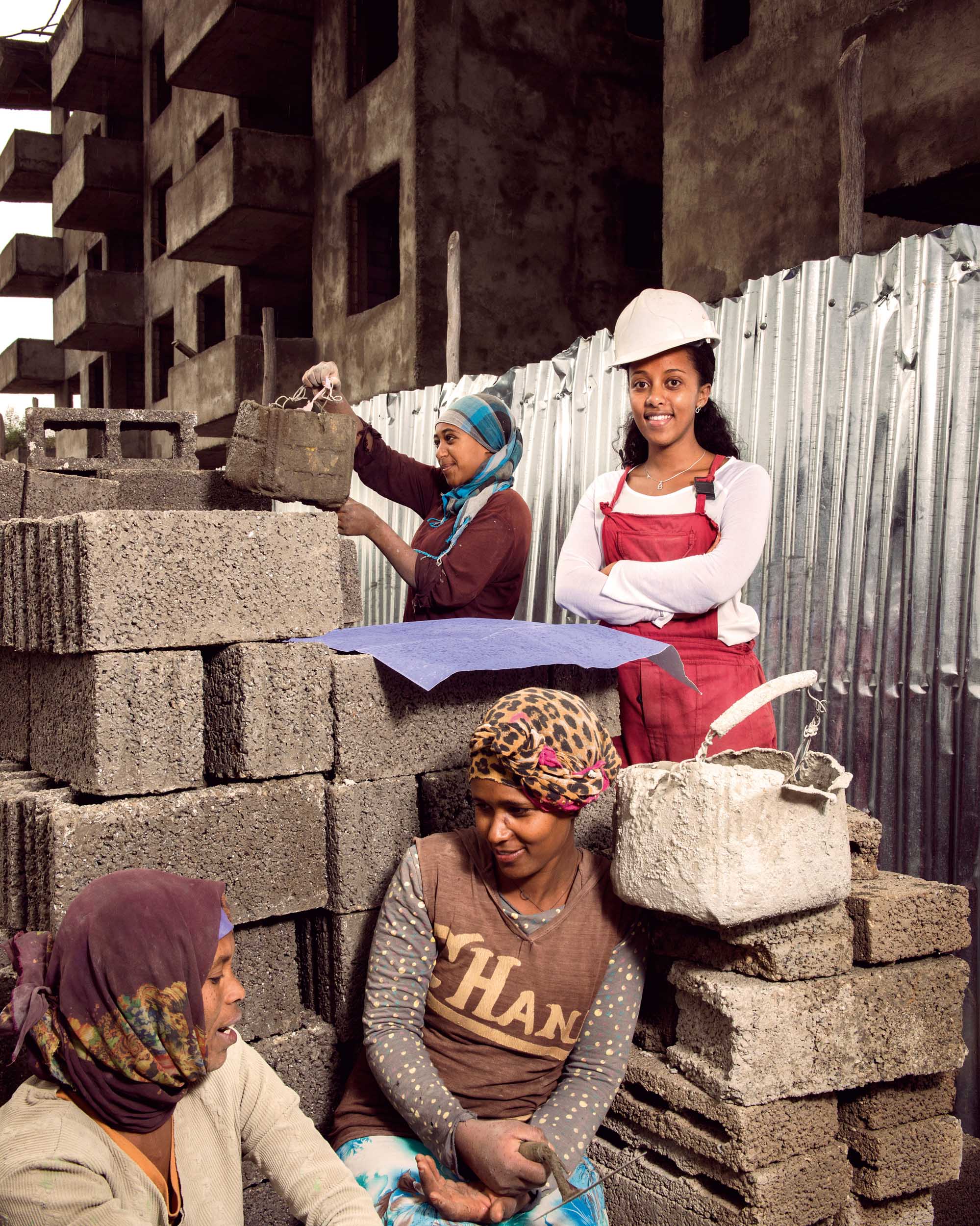

Helina Delelegn, 25

Helina is working for Impact International Real Estate. She is managing and supervising the real estates, specifically three building apartments that are under construction now in CMC site of Addis Ababa. She also handles other related activities at office such as building design and material breakdown

Helina Delelegn, 25

Helina is working for Impact International Real Estate. She is managing and supervising the real estates, specifically three building apartments that are under construction now in CMC site of Addis Ababa. She also handles other related activities at office such as building design and material breakdown

Benin. December 2015. The driver of this taxi-moto, also called zémidjan or zem (“get me there quick”) in Fon, the local language, wears the distinctive yellow shirt that is the drivers’ uniform. He pauses on a country road in Athiémé, Benin, on a bright November day, carrying all female riders.

Benin. December 2015. The driver of this taxi-moto, also called zémidjan or zem (“get me there quick”) in Fon, the local language, wears the distinctive yellow shirt that is the drivers’ uniform. He pauses on a country road in Athiémé, Benin, on a bright November day, carrying all female riders.

Niger. November 2015.Third grader Mariama Morou lives in Kosseye Satom, a village 15 kilometers from Niamey, the capital of Niger. Today she is helping her mother with household chores, because her teacher did not show up. Absenteeism among teachers is very common in Niger. Although the number of girls attending primary school has currently reached 80 percent, only 25 percent continue their studies into secondary school. According to a 2012 demographic study by the Ministry of Public Health, more than 75 percent of women in Niger are married before the age of 18, a rate the authorities hope to reduce by encouraging families to educate girls. At the start of the 20152016 school year, the Minister of Education kicked off an awareness campaign with the slogan “I’m standing up for girls’ education, because it changes lives.”

--

Mariama Morou est en classe de CE2 à l’école primaire du village de Kosseye Satom à une quinzaine de kilomètres de Niamey, la capitale du Niger. Aujourd’hui, elle aide sa maman à effectuer les travaux ménagers, son instituteur étant absent. L’absentéisme des enseignants est un phénomène très répandu au Niger. Si au niveau du primaire, le taux de fréquentation scolaire chez les filles atteint presque 80%, dans le secondaire, elles ne sont pourtant plus que 25% à poursuivre leurs études. Selon l’enquête démographique et de santé réalisée en 2012 par le ministère de la Santé publique, plus de 75% des femmes au Niger sont mariées avant l’âge de 18 ans, phénomène que les autorités nigériennes entendent combattre en incitant les familles à éduquer les filles. A l’occasion de la rentrée scolaire 2015-2016, le ministère de l’Éducation a lancé une campagne de sensibilisation sur le thème : « Pour la scolarisation des filles, je m’engage, car elle change la vie ».

Niger. November 2015.Third grader Mariama Morou lives in Kosseye Satom, a village 15 kilometers from Niamey, the capital of Niger. Today she is helping her mother with household chores, because her teacher did not show up. Absenteeism among teachers is very common in Niger. Although the number of girls attending primary school has currently reached 80 percent, only 25 percent continue their studies into secondary school. According to a 2012 demographic study by the Ministry of Public Health, more than 75 percent of women in Niger are married before the age of 18, a rate the authorities hope to reduce by encouraging families to educate girls. At the start of the 20152016 school year, the Minister of Education kicked off an awareness campaign with the slogan “I’m standing up for girls’ education, because it changes lives.”

--

Mariama Morou est en classe de CE2 à l’école primaire du village de Kosseye Satom à une quinzaine de kilomètres de Niamey, la capitale du Niger. Aujourd’hui, elle aide sa maman à effectuer les travaux ménagers, son instituteur étant absent. L’absentéisme des enseignants est un phénomène très répandu au Niger. Si au niveau du primaire, le taux de fréquentation scolaire chez les filles atteint presque 80%, dans le secondaire, elles ne sont pourtant plus que 25% à poursuivre leurs études. Selon l’enquête démographique et de santé réalisée en 2012 par le ministère de la Santé publique, plus de 75% des femmes au Niger sont mariées avant l’âge de 18 ans, phénomène que les autorités nigériennes entendent combattre en incitant les familles à éduquer les filles. A l’occasion de la rentrée scolaire 2015-2016, le ministère de l’Éducation a lancé une campagne de sensibilisation sur le thème : « Pour la scolarisation des filles, je m’engage, car elle change la vie ».

In Niger, products based on local grains are prepared with devices such as this processing unit for black-eyed peas in Guéchémé, in the Dosso region, where women organized their own cooperative in 2003. Within the group, which is named Tashi ga Kanki(Rise Up to Insure Your Future!), they share tools of the trade, exchange know-how and help each other out when the rains come. Each woman saves part of her earnings, and when food is sparse, the 40 members distribute benefits in the form of credit, so the women can survive until the next crop. After the harvest, they must repay the amount used as credit to the group, which then buys sacks of black-eyed peas for the women to turn into couscous, cookies or noodles. This year, their savings have already covered three tons of the legumes, out of a target of five tons. For Maimouna (in the foreground at left), born during the great famine of 1984, food insecurity is a disaster to be avoided at all costs.

In Niger, products based on local grains are prepared with devices such as this processing unit for black-eyed peas in Guéchémé, in the Dosso region, where women organized their own cooperative in 2003. Within the group, which is named Tashi ga Kanki(Rise Up to Insure Your Future!), they share tools of the trade, exchange know-how and help each other out when the rains come. Each woman saves part of her earnings, and when food is sparse, the 40 members distribute benefits in the form of credit, so the women can survive until the next crop. After the harvest, they must repay the amount used as credit to the group, which then buys sacks of black-eyed peas for the women to turn into couscous, cookies or noodles. This year, their savings have already covered three tons of the legumes, out of a target of five tons. For Maimouna (in the foreground at left), born during the great famine of 1984, food insecurity is a disaster to be avoided at all costs.

Hadiza (center) prepares a family meal, aided by her daughters Nadia, 4, and Layhanatou, 10, who grind millet in a wooden mortar. At age 32, Hadiza has six children, four sons and two daughters. She lives in Rabé, a village 25 kilometers east of Dosso comprised of circular huts made of mud brick covered with straw, and granaries topped with straw hats. The little girls help their mother with chores while the men work in the fields. The village marabout sees to the children's education.

The most widely grown grain in Niger, it is the country's dietary mainstay. Threshing, hulling and grinding millet by hand makes for a long, exhausting workday. The Ministry of Population, Advancement of Women and Protection of Children has made it a priority to lighten women's workloads by providing them access to mills, hullers and water sources. In the countryside, however, many Niger women have no choice but to use the traditional methods.

Hadiza (center) prepares a family meal, aided by her daughters Nadia, 4, and Layhanatou, 10, who grind millet in a wooden mortar. At age 32, Hadiza has six children, four sons and two daughters. She lives in Rabé, a village 25 kilometers east of Dosso comprised of circular huts made of mud brick covered with straw, and granaries topped with straw hats. The little girls help their mother with chores while the men work in the fields. The village marabout sees to the children's education.

The most widely grown grain in Niger, it is the country's dietary mainstay. Threshing, hulling and grinding millet by hand makes for a long, exhausting workday. The Ministry of Population, Advancement of Women and Protection of Children has made it a priority to lighten women's workloads by providing them access to mills, hullers and water sources. In the countryside, however, many Niger women have no choice but to use the traditional methods.

These young soccer players are training at Kégué Stadium, the largest arena in Togo's capital, Lomé. As students at the Institut National de la Jeunesse et des Sports (National Institute for Youth and Sports), they are pursuing a curriculum that will enable them to teach physical education and sports. Rakietou Kparanta (center), 22, plays for Friends of the World, the top women's soccer team in the country. Soccer is my passion, she confides, but it has also been a way for me to build self-confidence."Women's soccer is booming in Togo, which boasts 49 women's teams, including 16 professional clubs, yet it remains severely underfunded and receives no subsidies from national authorities. "Any support we have is due to the good will of a few organizations that mount tournaments, laments the team's trainer, Kaï Tomety.

A former soccer champion, Ka� does what she can to promote women� soccer in Togo.

These young soccer players are training at Kégué Stadium, the largest arena in Togo's capital, Lomé. As students at the Institut National de la Jeunesse et des Sports (National Institute for Youth and Sports), they are pursuing a curriculum that will enable them to teach physical education and sports. Rakietou Kparanta (center), 22, plays for Friends of the World, the top women's soccer team in the country. Soccer is my passion, she confides, but it has also been a way for me to build self-confidence."Women's soccer is booming in Togo, which boasts 49 women's teams, including 16 professional clubs, yet it remains severely underfunded and receives no subsidies from national authorities. "Any support we have is due to the good will of a few organizations that mount tournaments, laments the team's trainer, Kaï Tomety.

A former soccer champion, Ka� does what she can to promote women� soccer in Togo.

Belindah Malutoava, 21, is surrounded by some of the 200 chickens she keeps in the Kikaaya neighborhood of Kampala, Uganda. The single mother of a young toddler has a business supplying eggs and meat to supermarkets. She got her start with the help of an aunt and a loan through the Kikaaya girls club microfinance group. Women who grew up 10 years ago were supposed to be housewives so they didn't need to work but, me, I'm different. I'm working. I make my own money,says Malutoava. She says she is determined to continue her education and to yet somewhere. In five years time I want to have a very big farm, a big, big farm, with so many chickens, like a thousand chickens. Yeah, that what I want.

Belindah Malutoava, 21, is surrounded by some of the 200 chickens she keeps in the Kikaaya neighborhood of Kampala, Uganda. The single mother of a young toddler has a business supplying eggs and meat to supermarkets. She got her start with the help of an aunt and a loan through the Kikaaya girls club microfinance group. Women who grew up 10 years ago were supposed to be housewives so they didn't need to work but, me, I'm different. I'm working. I make my own money,says Malutoava. She says she is determined to continue her education and to yet somewhere. In five years time I want to have a very big farm, a big, big farm, with so many chickens, like a thousand chickens. Yeah, that what I want.

/

MosaïqueMosaic

LégendeLegend