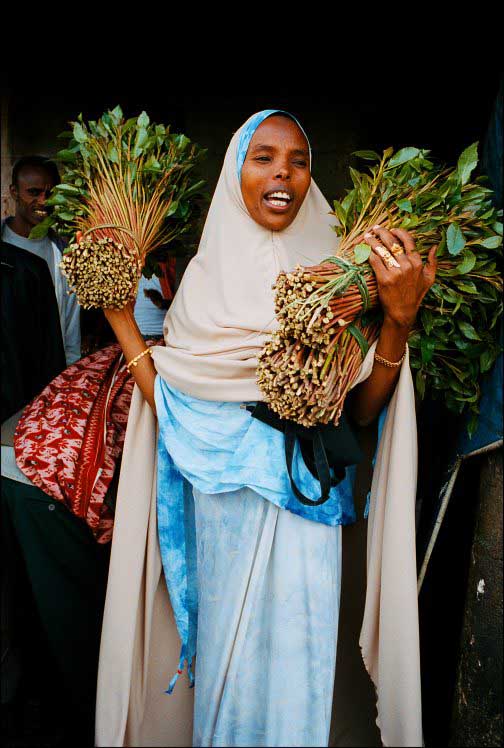

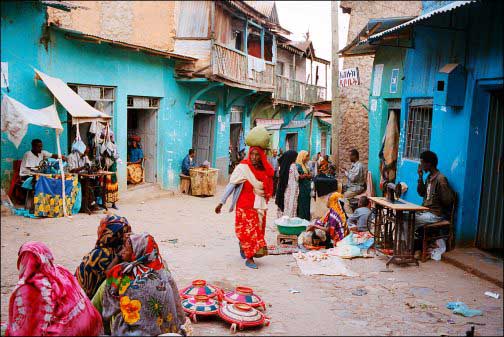

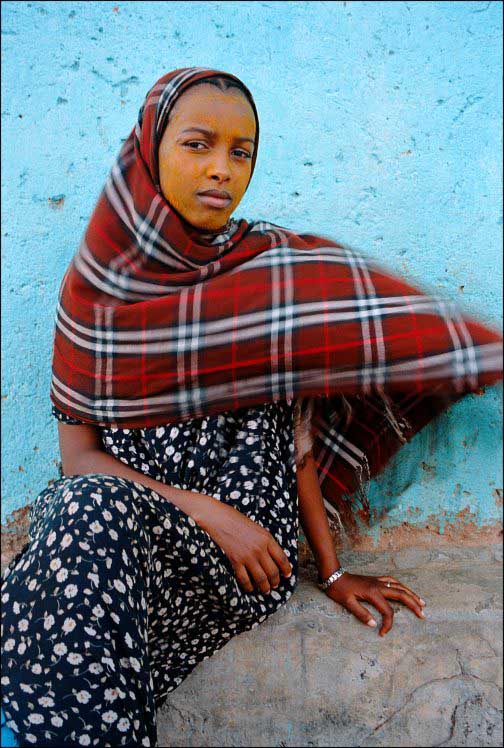

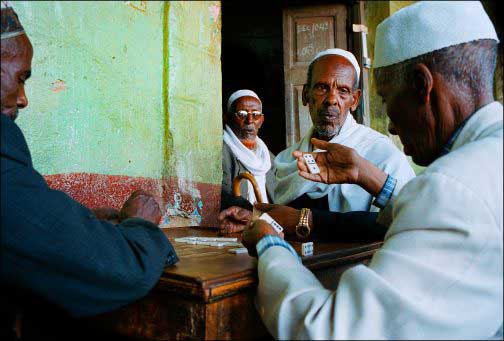

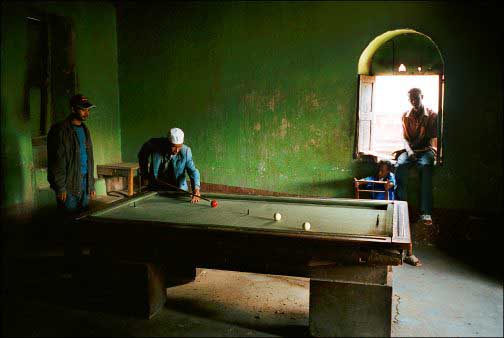

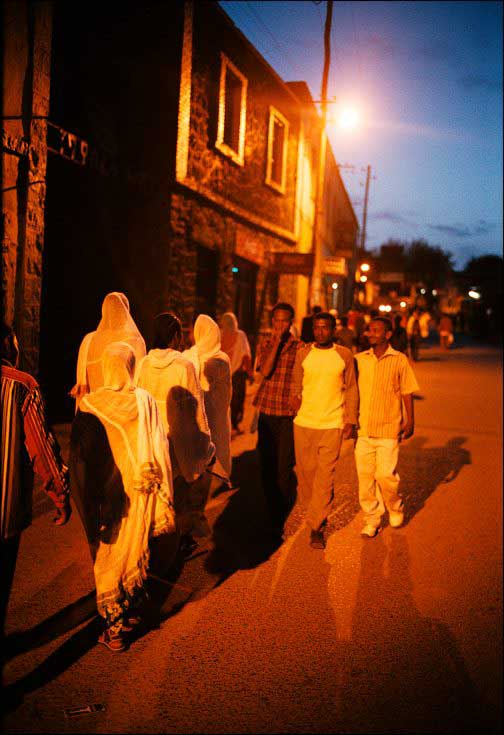

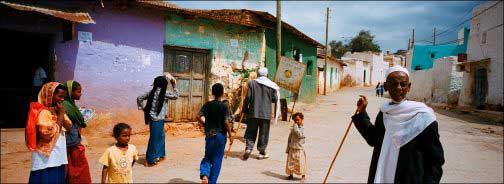

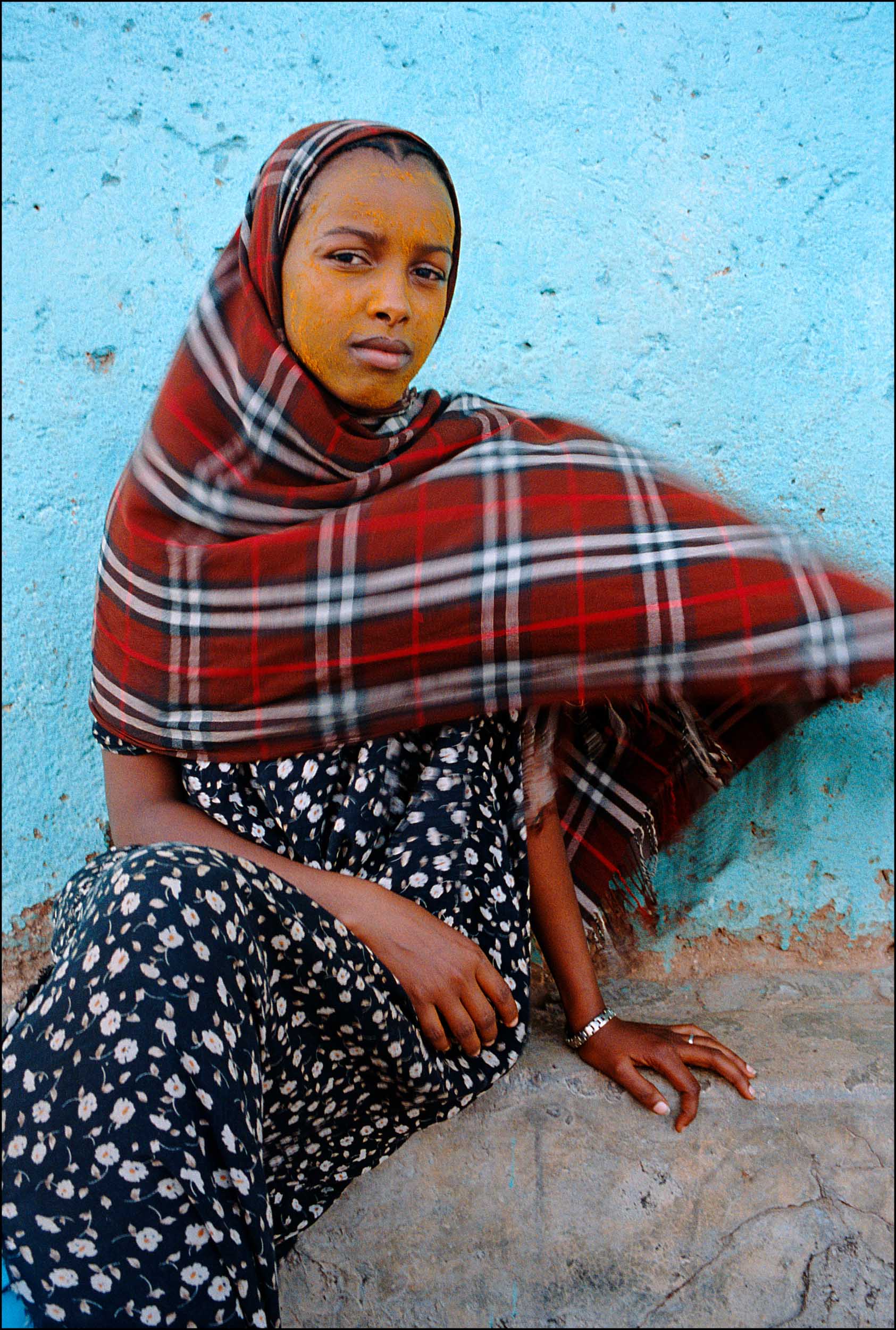

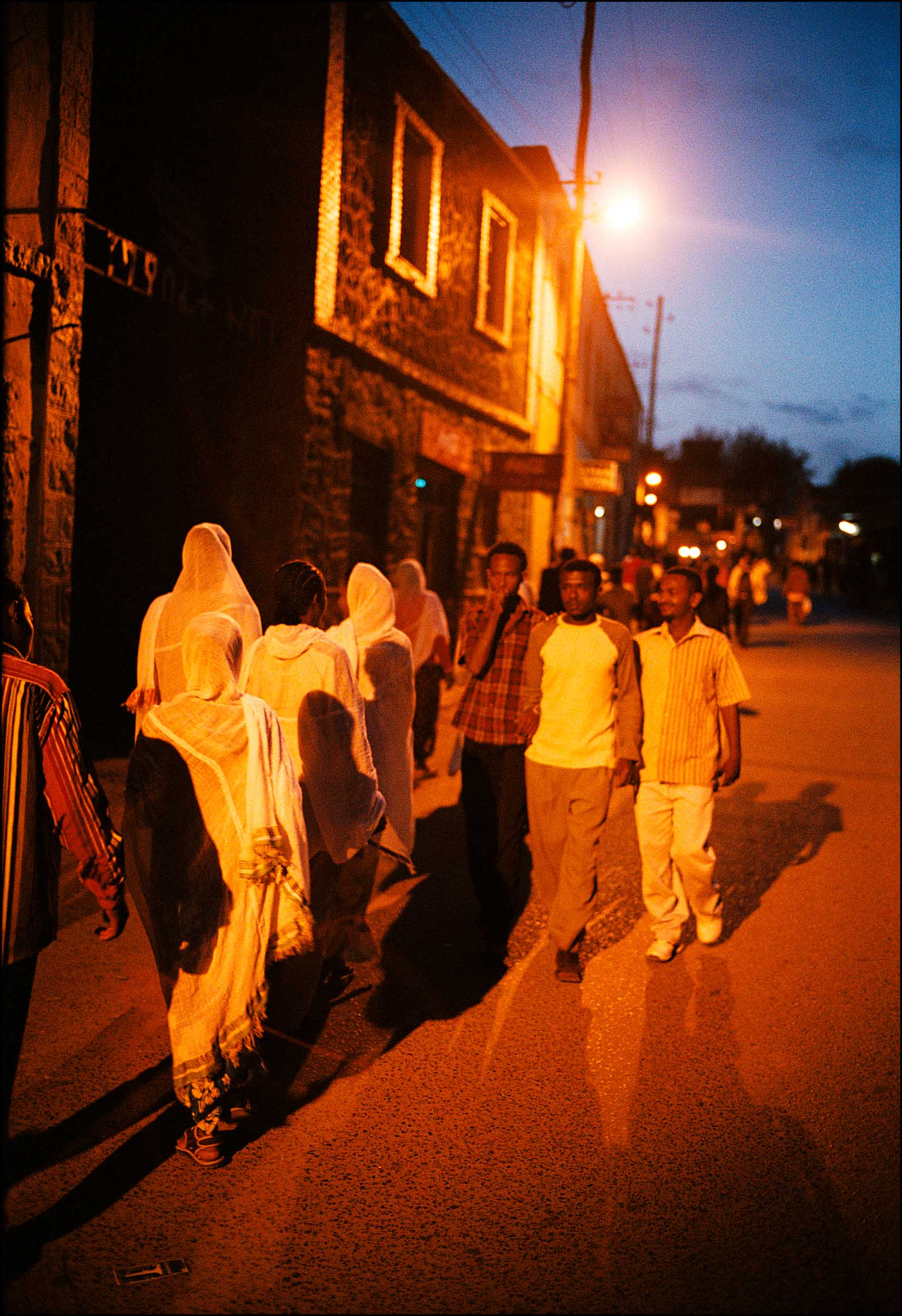

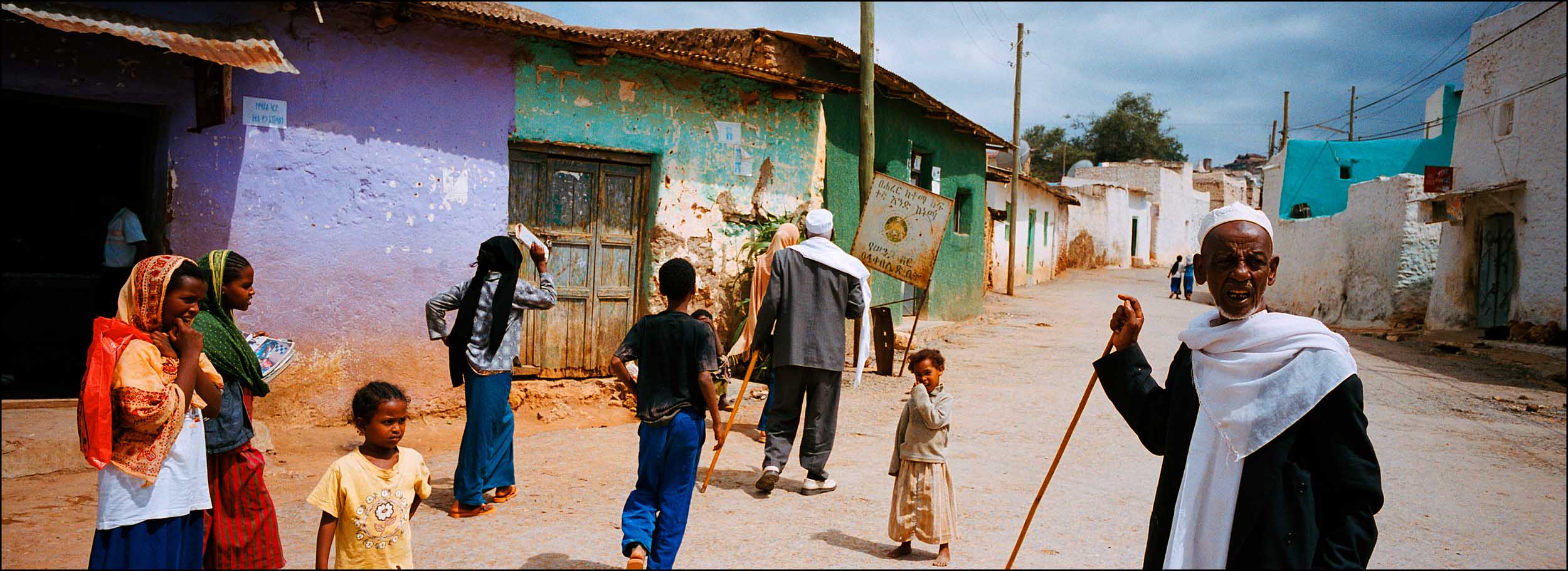

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

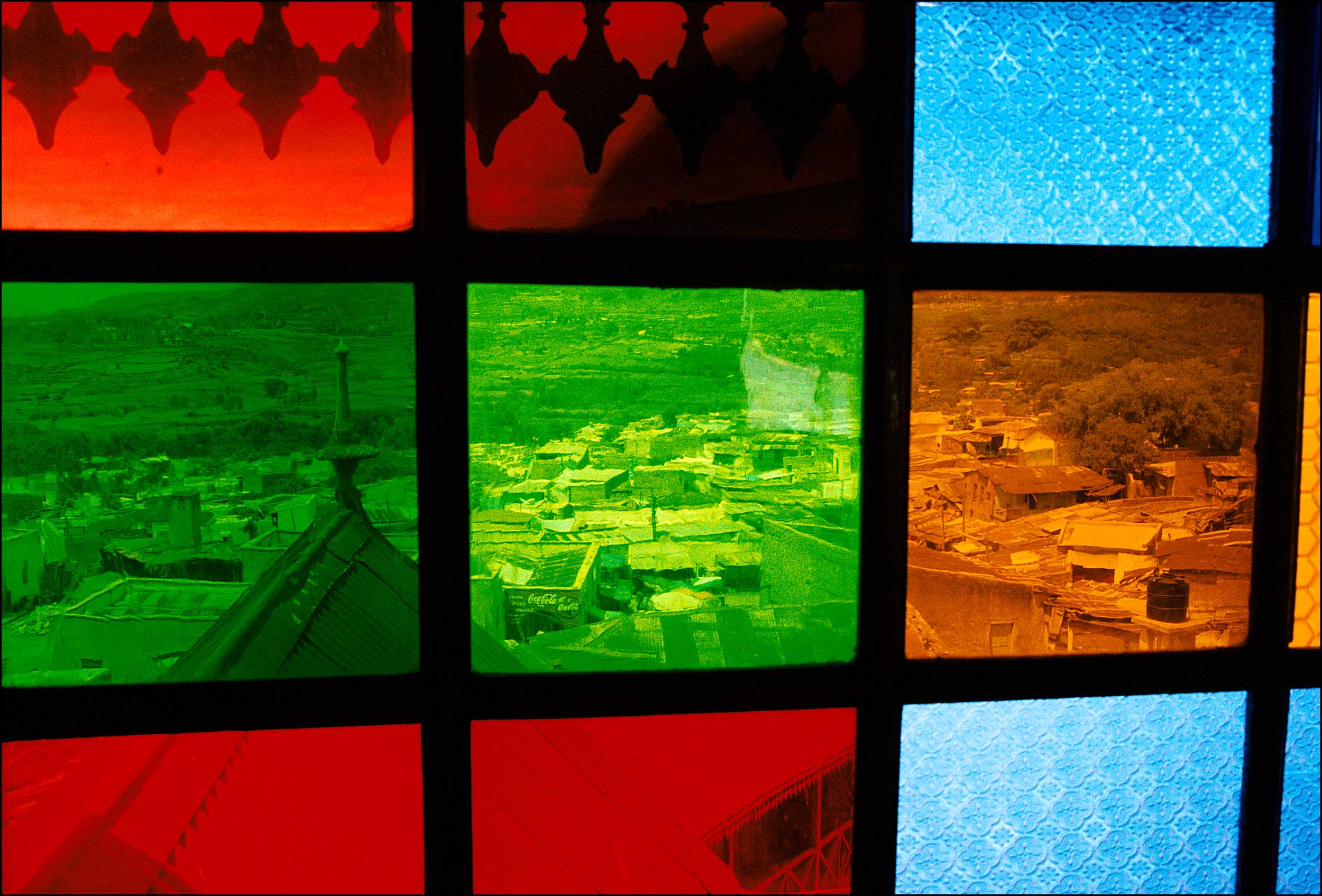

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

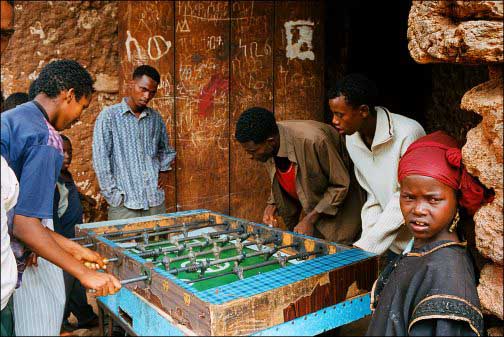

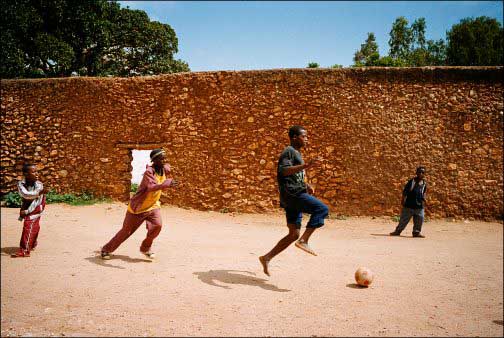

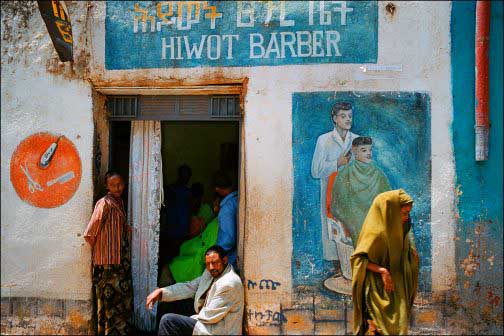

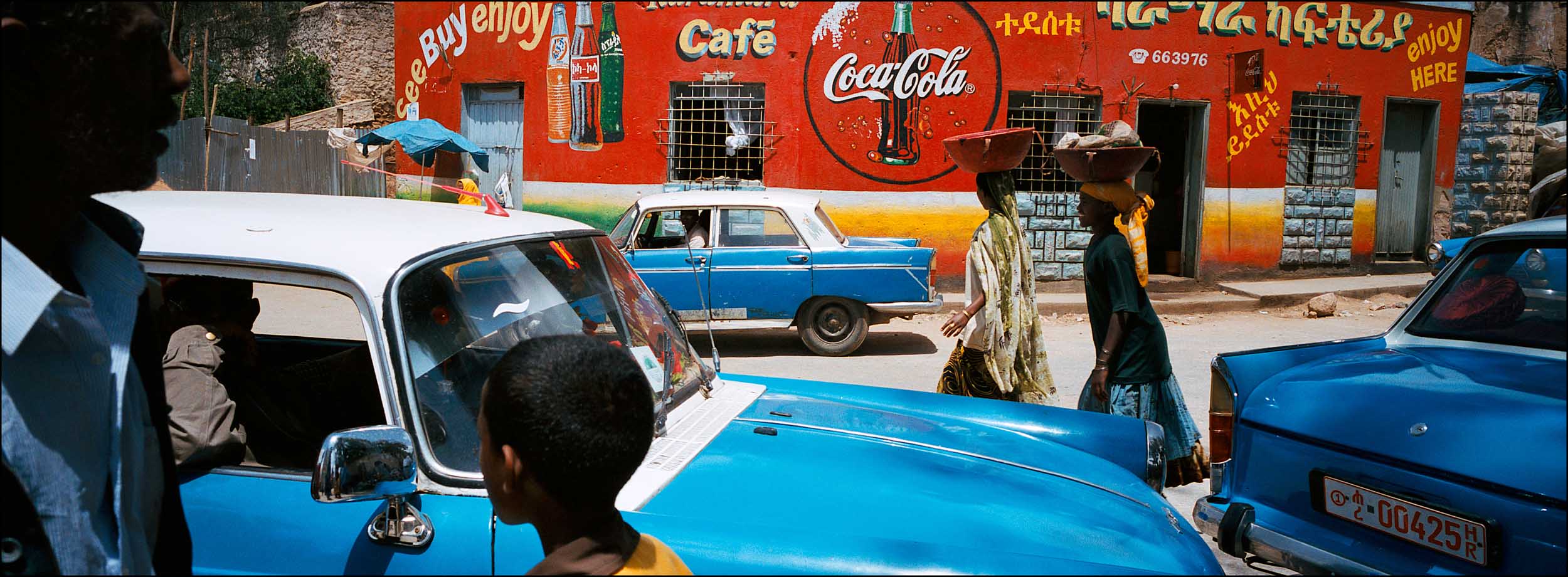

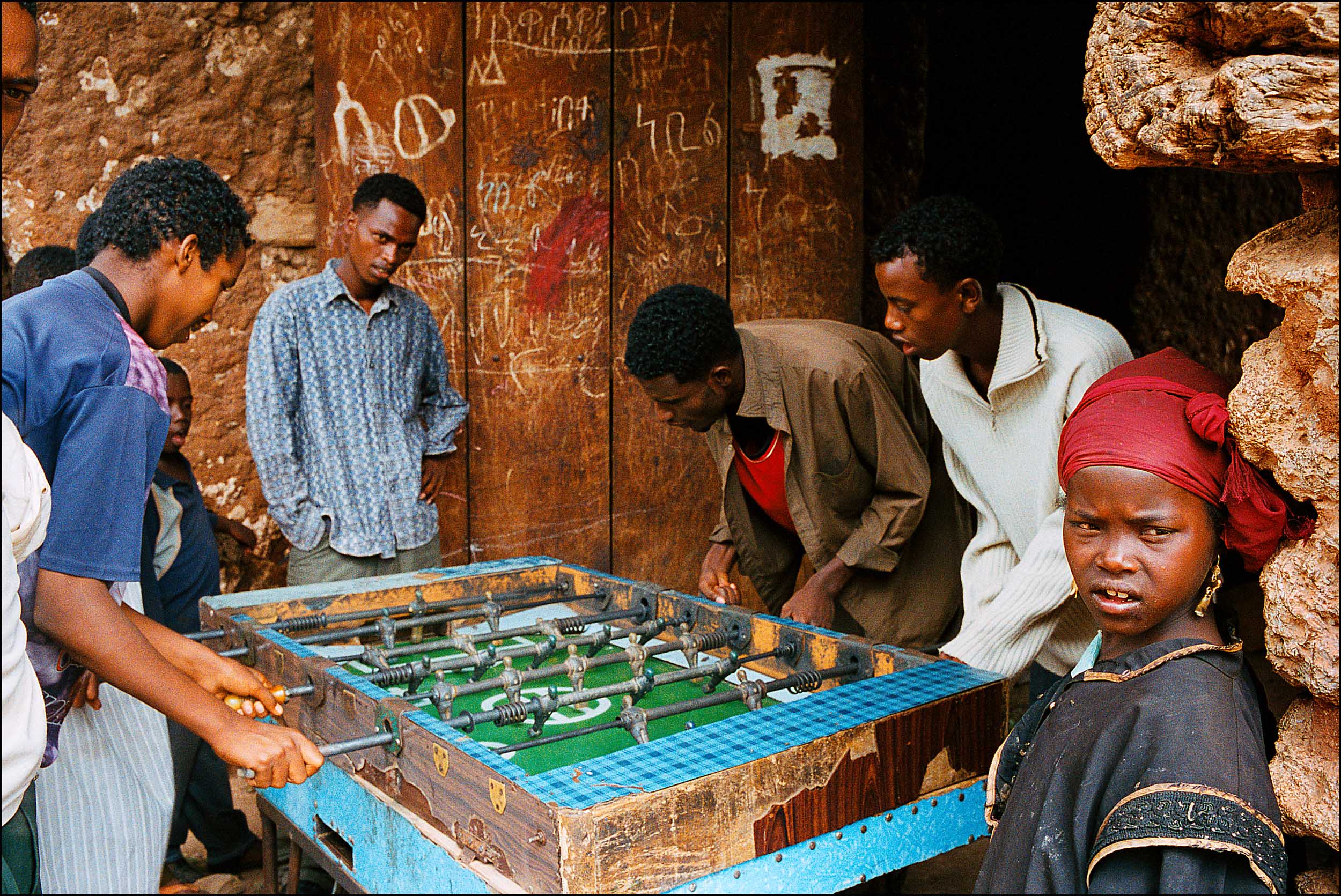

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

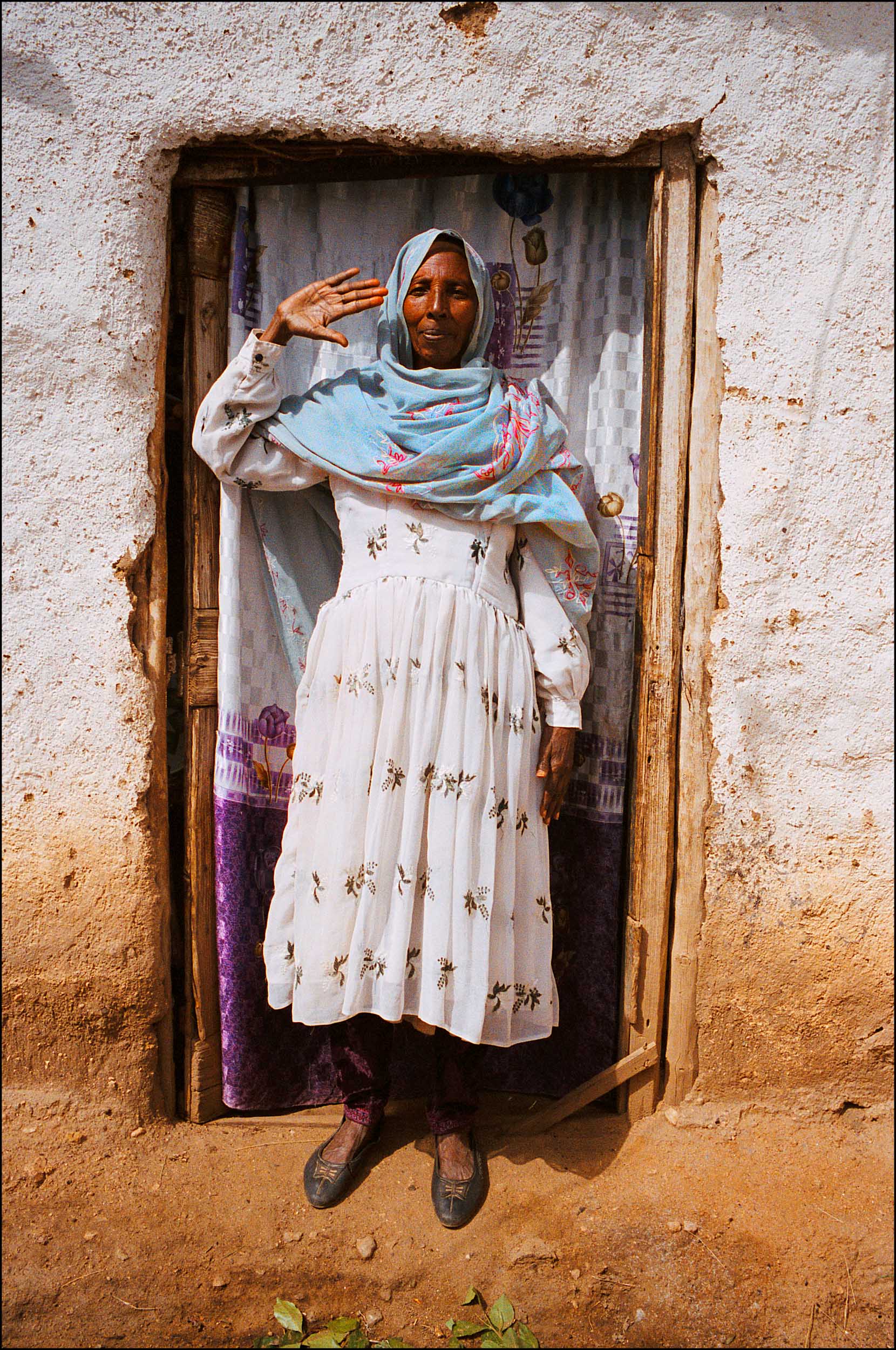

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

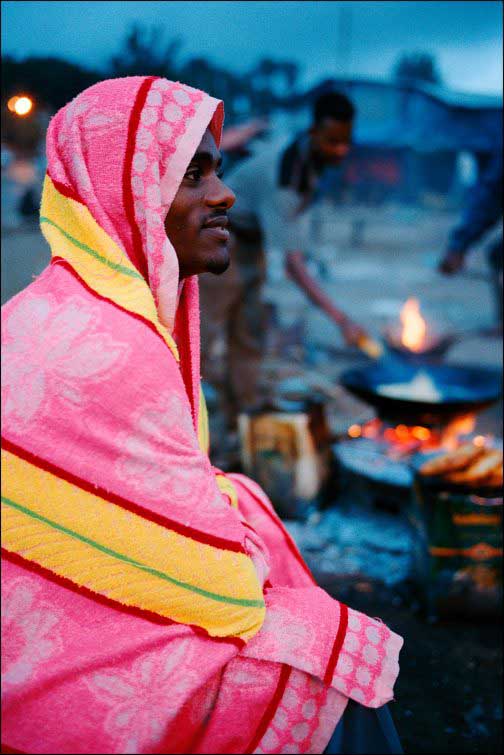

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

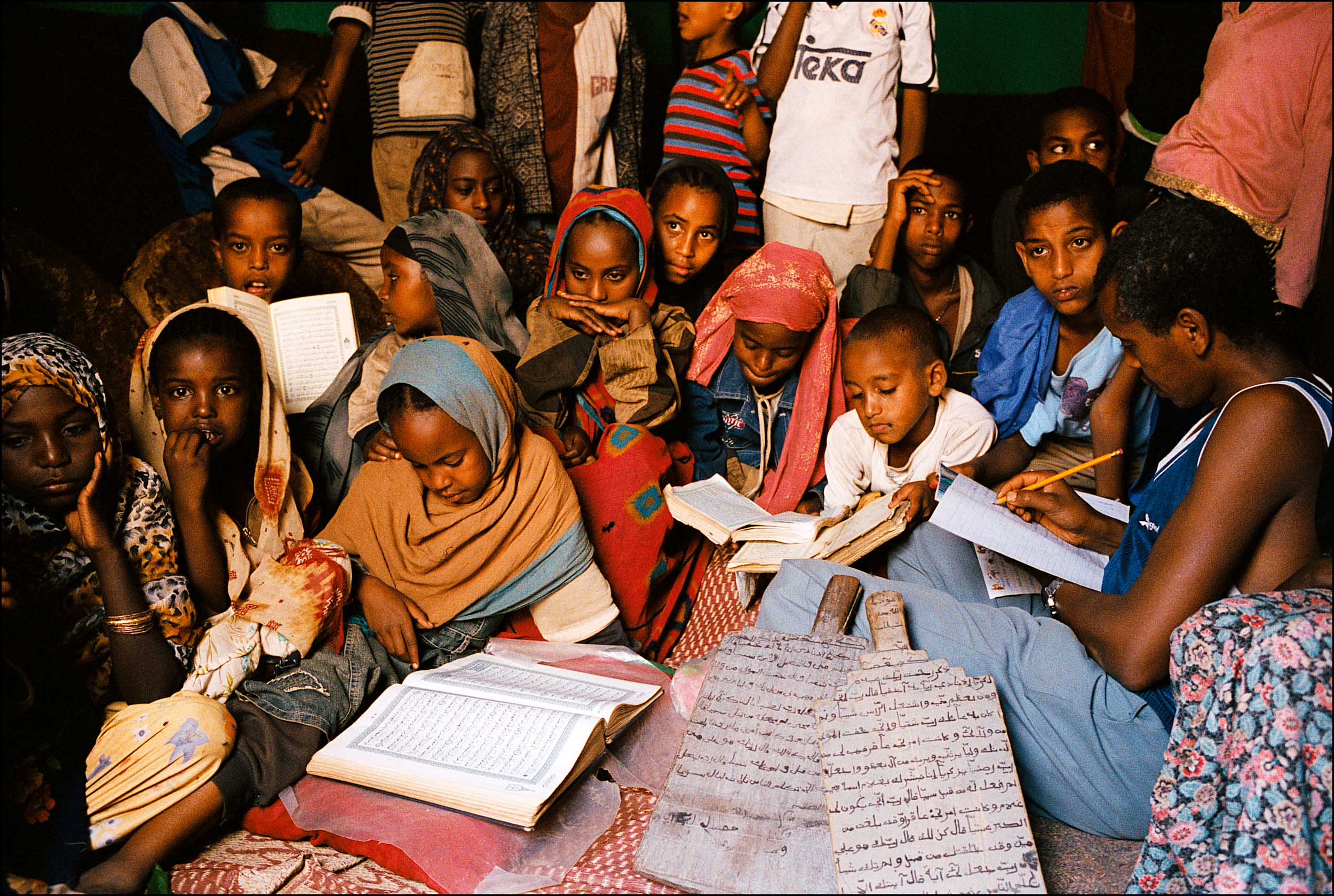

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.

The French poet, who turned his back on literary stardom and became a gunrunner in Harar, didn't actually live in the large ornate house standing today.

This was built by an Indian merchant on the site of an earlier house where Rimbaud apparently lived.

Inside, on the second floor, a photographic exhibition of turn-of-the-20th-century Harar shows the strange world Rimbaud encountered -- some scenes with similarities to the present day.

Despite the Jugal containing 82 mosques and this being a return trip I couldn't seem to find any of them as I zigzagged among pastel-col

The ancient walled city of Harar in eastern Ethiopia is a hard place to forget: the silent maze-like alleys, the scents of the markets, the handsome women carrying intricately woven baskets atop heads, the muezzins calling the Muslim faithful to prayer.

From my hotel room's small balcony I could see the Asmaddin Beri (beri means gate, as well as, rather more grandly, portal).

It's one of six punctuating the thick five-meter-high walls running 3.5 kilometers around the Jugal, the name for the 16th-century fortification that lies within the modern town that developed from the 19th century onward.

Once through the Asmaddin portal the 21st century vanished, replaced by a sense of antiquity and a heaving, shambolic outdoor market, one of many dotted around the Jugal.

Harari women in colorful dresses squatted beside neat piles of onions, tomatoes, green peppers, bananas and more.

Sweet smells wafted from where women sold pots of itan incense, while samosas cooking on small stoves and baskets full of fresh bread rolls added to the pleasant stimulation.

"Feranju! Feranju! Amantekhi?!" the women called in the local Harari dialect, which roughly translates as: "Foreign guy, foreign guy, how are things?!"

On Mekina Girgir, a narrow, atmospheric street packed with tailors' workshops and men at sewing machines, one tailor looked up from his machine to point the way to what's known as Arthur Rimbaud's house.